Women comprise just 8 per cent of Australia’s prison population, yet they are the fastest growing cohort amid the country’s mass imprisonment crisis. Multiple organisations and researchers are calling for an overhaul of Australia’s justice system to help combat the issue. (Image: Raw Pixel)

By Jessica Dempster | @dempsterjess_

On a Friday afternoon, following a particularly miserable week of torrential rain and wintery weather in Adelaide, a small group of women trail out of the Semaphore Uniting Church.

The group is dispersing from the second bi-weekly meeting run by the Adelaide local non-profit volunteer community group, Seeds of Affinity who host meetings at the church every Tuesday from 11am to 3pm and Friday 12pm to 3pm.

Seeds of Affinity was established in 2006 by women, for women who have experienced life in prison. The group meets twice a week to ensure those who need it have access to resources and support so they can lead successful lives.

Founding member Linda Fisk says, “SOA was born out of a gap in services provided for women both in prison and exiting prison.”

“Women didn’t feel like they fit into the mainstream support services offered by prisons and the Australian Government,” Fisk says.

“A lot of women were getting out and returning to prison straight away due to feelings of loneliness and isolation and that’s how SOA came to be.

“Since then, we’ve grown and evolved to where we do a lot of lobbying and activism.

“We’re an abolitionist organisation so we really believe de-incarceration is the best thing for our women.

“We believe women do not really need to be in prison at all and if they were supported more in the front end, they wouldn’t end up there in the first place.

“All the resources spent on the prison system could be put to far better use supporting women and children within the community.”

The forgotten pandemic

As the majority of Australians work diligently to return to normal after three years of living through the COVID-19 pandemic, the women behind Seeds of Affinity and countless other organisations and researchers are fighting another epidemic: the mass imprisonment of Australian women.

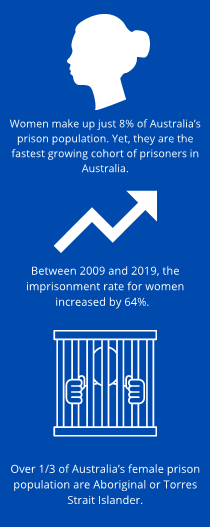

Between 2009 and 2019, the imprisonment rate for women in Australia increased by 64 per cent. Comparatively, the rate for male imprisonment increased by 45 per cent during the same decade.

Researchers have proposed two possible causes for the increase. Either women have begun to commit more serious crimes, warranting harsher punishments, or law enforcement and the justice system have started imposing more severe penalties on minor crimes.

Emeritus Professor of Law and Criminal Justice at the University of South Australia, Rick Sarre says its most likely a combination of the two.

“A significant factor I think is the fact that courts are no longer taking some paternalistic view that women are committing crimes because they are being led by men,” Sarre says.

“Nowadays women are getting the same punishments as men.

“Parliaments are also passing more severe laws. Every time someone says something is going wrong, someone else says it can be fixed by imposing a harsher punishment.”

Do the crime, do the time

These harsher punishments and the documented steady rise in the level of imprisonment in Australia for both men and women are fundamentally a result of Australia’s “tough on crime” approach. In fact, Australia’s rate of growth in imprisonment is significantly out of line with other developed countries according to Australia’s Productivity Commission.

Commissioner Stephen King says these numbers imply the ongoing presence of a “crime wave” in Australia, but data examined by the Productivity Commission suggests otherwise.

The rate of offending in Australia between 2010-2020 decreased by 18 per cent yet the imprisonment rate rose by 25 per cent.

Tightening bail laws and an increase in unsentenced prisoners being held in custody on remand are some factors experts say contribute to the rising incarceration rates in Australia.

However, the Productivity Commission’s 2021 research paper that delves deeper into “Australia’s prison dilemma” says there is no simple driving factor as to why Australia’s imprisonment rates continue to rise.

The women behind the bars

Unlike men, women in prison are typically incarcerated for non-violent offences, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

The most common charges for women in prison are substance related offences, traffic incidents, fraud and theft.

Many women in Australian prisons come from unsettled or difficult childhoods that lead to equally, if not more so, tumultuous adult lives.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare says, “Women in prison often come from disadvantaged backgrounds, with histories of poverty, domestic violence, social deprivation and childhood trauma.”

A study into how the rising rates of women in prison are becoming a serious public health issue also reveals that women in prison have disproportionately higher rates of substance-use disorders compared to both men in prison and women in the general population.

Women in prison are also characterised by extensive histories and experiences with trauma and mental health struggles. These experiences often predispose individuals to substance abuse and engagement in other criminal activities.

Just over a third of Australia’s female prison population are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, despite Indigenous women comprising only 2 per cent of the general female population. First Nations women are the fastest-growing prison population in Australia, being incarcerated at a rate 20 times more than the rate of non-Indigenous women. The situation has been decreed a national incarceration crisis.

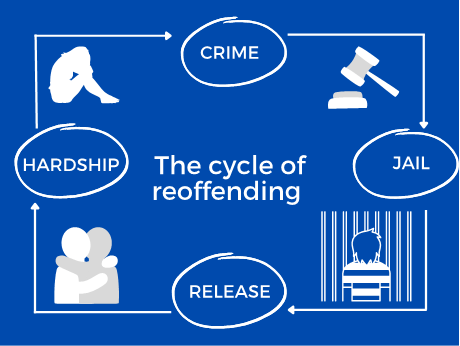

In 2020, half the population of female prisoners also had a prior imprisonment on their record. In fact, recidivism rates in Australia are on the rise with almost 3 in 4 prison entrants reporting they’d previously been incarcerated.

Linda Fisk says this occurs because “women learn to be helpless in prison; they have no power, no way to resist.”

“It’s so overpowering and overwhelming they just surrender to it.

“When they get out, they’ve lived in that state of helplessness for so long that it’s very hard to take their destiny into their own hands.

“That’s how the cycle of offending becomes a problem.”

Jailing is failing

The Productivity Commission says, “As a policy, imprisonment serves multiple objectives: deterring crime, removing dangerous individuals from the community, punishing, and rehabilitating offenders, and supporting the rule of law”.

However, over the past decade, due to many failings, many Australians have begun demanding the reforming of the Australian justice and prison system.

“Jailing is failing, and it has been for a long time,” Sarre says.

“We’re coming to a crunch point now where we just simply can’t afford to keep putting people behind bars.”

The overall consensus from experts, advocacy groups, and ex-prisoners alike is that Australia as a country must rethink the response to women’s offending.

Advocacy and campaign coordinator for the Justice Reform Initiative (JRI), Hannah March says jailing is failing a wide range of cohorts across Australia.

“It’s failing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it’s failing youth, women, those living with mental illness and cognitive disabilities, taxpayers, disadvantaged people, and victims of crime,” March says.

“It’s failing as a deterrent and it’s failing to rehabilitate people.

“The bottom line is it’s failing to keep the community safe, and it’s traumatising people in the process.”

The Justice Reform Initiative is focused on bringing awareness to the issue of mass-imprisonment through using evidence-based policies. Hannah says the group is trying to get through to the Australian Government what many Australians have been telling them for a long time.

“There’s a lot of organisations doing great work in this space and we’re very mindful of not wanting to come over top of them and say we’ve got all the answers because we don’t,” March says.

“There’s a lot of people out there working hard every day to keep women out of prison and help those who have been recently released.

“They’re so busy doing that that they’re not able to spend money on advocacy or putting out press releases about their amazing work, the success their achieving, or the money they need, so we’re really hoping to work in partnership with these groups to amplify their voices and efforts.”

Hope for the future

One of the organisations the JRI hopes to establish partnership with and promote is Seeds of Affinity.

Both organisations agree that the Australian Government desperately needs to do something to start reducing the number of women in Australian prisons.

Fisk says, “The current [prison] model is just not a good model”.

“It’s just not a good idea to have young women in prison with older women that have adjusted to and been affected by the prison system.

“It’s like sending kindergarten kids to school with high school kids. We just wouldn’t do that to our children, so why are we doing it to young girls and women?”

Fisk says the current prison model also does not provide women with the access to tools and resources men receive to help them gain skills and experiences that’ll help them outside of prison.

“People will tell you the reason why women don’t get the same treatment as men is because of the numbers, but that shouldn’t be a reason to not give women any opportunities while in prison,” she says.

While Seeds of Affinity continues to advocate and provide support and information for women re-joining society after imprisonment, the Justice Reform Initiative is committed to reforming the criminal justice system and eventually putting an end to Australia’s excessive imprisonment.

March says the Justice Reform Initiative “thinks the solution is justice reinvestment: investing the money that gets spent on cycling people through prison on services in the community to help people with what we know are the entrenched discrimination and other forms of exclusion from mainstream society that come from, and lead people to, going to prison.”

“It’s the homelessness, substance abuse, and all things that could be combatted with more appropriately so people can be appropriately supported in the community rather than from inside correctional institutions.”