In an increasingly competitive job market, the inevitably of completing unpaid internships is on the rise. But is the system creating better job opportunities for young people or simply extorting them for free labour? (Image: from Headway via Unsplash)

By Lauren Wisgard | @LaurenWisgard

In today’s increasingly competitive job market, the majority of young Australians are taking part in unpaid internships to acquire must-have experience for their resumes.

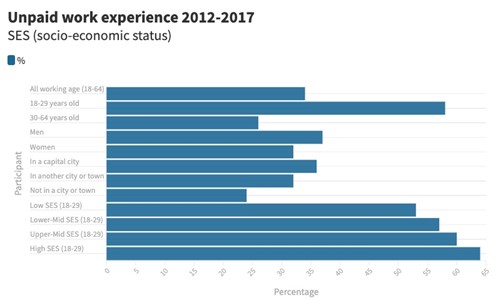

A 2017 survey funded by the Department of Employment revealed that 58 per cent of 3800 participants, who were between the ages of 18 to 29, had participated in unpaid work experience.

The findings, as reported by The Conversation, detailed that 36 per cent of respondents said their most recent unpaid internship lasted over a month.

One in five reported they had undertaken five or more unpaid internships in the previous five years.

(Image: The Conversation)

As the inevitably of completing unpaid internships rises, we must ask: is the system creating better job opportunities for young people, or simply extorting them for free labour?

Furthermore, underneath a guise of career development and equal opportunity, are we seeing the broadening of the gap between the privileged and the less fortunate?

By speaking to three university students about their experiences, this issue becomes greyer than it appears on the surface.

Sarah* is a Law and Commerce (Marketing) student who has so far completed five internships: some paid, some not.

Her most recent unpaid internship in a law role is one she feels lucky to have and is the first to admit it is a privileged position.

“I almost feel as though they are doing me a favour by hosting me because of how much I’ve learned during the internship,” Sarah says.

She says this internship, which is giving her class credit and is on a short-term basis, is not one she would expect to be paid for but is aware that she is lucky that money is not a massive concern for her at this point in her life.

“I live at home and have very few day-to-day living expenses, so I’m able to sacrifice paid work for unpaid internships frequently. I also have parents that would happily financially support me if I wasn’t able to afford something,” Sarah says.

“A lot of the opportunities in law are unpaid and given the high number of law students and graduates and the limited job opportunities, firms are able to exploit students’ desperation for work experience.”

She says the requirement of unpaid work in elite professions such as law will further perpetuate the inaccessibility of the work.

“It feels like degrees like law, and subsequently the legal profession, will continue to be dominated by upper middle-class students who can afford to undertake unpaid work. In my opinion, fields like law desperately need diverse perspectives and experiences.”

Sarah’s concerns are echoed by the findings of the 2017 survey, which highlighted that professions such as journalism, law, politics, and finance are dominated by those from privileged backgrounds.

The results found that this is because wealthy families can afford to support their children as they undertake unpaid work experience.

While Sarah isn’t exactly sure how to make internships a more even-levelled playing field for students of different socio-economic backgrounds, she says unpaid internships need to stop being the norm.

“Universities and organisations need to stop normalising unpaid internships. In certain circumstances, unpaid internships make sense, like in my current role, but this should be the exception to the rule as opposed to widely practiced,” she says.

“More organisations should be offering paid placements because it benefits them as well. I’ve felt more motivated to produce high quality work in my paid positions.”

Denae has been doing a “voluntary internship” at the RSPCA for the last two years because, after finishing her communication and media degree, she discovered that getting a job in her desired field was harder than she anticipated.

“I started at the very end of my degree; it wasn’t part of the degree. I sort of volunteered to do it with them because my actual internship got cancelled because of COVID and I’ve sort of stuck with them because I’ve had trouble getting work in that area,” Denae says.

“I started [applying] basically when I finished my degree. I started looking for jobs in [the] marketing and communications sort of area. After a couple of months when I wasn’t really getting much back, I had to sort of broaden my horizons and apply for hospitality and retail.”

Because of the length of time she’s been there, Denae’s role has transformed from “voluntary intern” to “volunteer”, despite her tasks being what an employee would be performing.

“I do their marketing and social media … I am basically working as an employee without the pay,” she says.

“I’m not going to get a job at RSPCA; they very much rely on volunteers and have no funding.”

The question is: is it legal for a company to let a “volunteer” or “voluntary intern” do the same work an employee would without payment?

The Fair Work Ombudsman offers some criteria to help assess whether a company is hosting an internship that is unlawful.

According to the website, an unpaid internship is acceptable if the intern is a student or there’s no employment relationship.

To determine the lawfulness of an unpaid internship, you need to consider if the work being asked of the intern is normally done by paid employees, as well as the length of the internship.

If the business or organisation is the one benefiting from the arrangement, the person is more likely to be classified as an employee rather than an intern.

Looking at all these factors, it seems obvious that Denae should be classed as an employee and receive financial compensation.

However, as the organisation refers to her as a volunteer now and not as an intern, the law says the individual does not need to be paid as the parties did not intend to create a legally binding employment relationship.

But just because neither of these scenarios are illegal, it doesn’t mean they’re not exploitative.

For recent journalism graduate Ashlea, her internship experience was without mentorship or training.

She admits the lack of support left her feeling that internship programs are exploiting the free labour an intern can provide by capitalising on their need to complete placement as part of their degrees.

“Internships can be great for students as they get experience, work out what job they want to do or don’t want to do, and they develop a wonderful portfolio,” she says.

“But the media companies we work for during our internships are capitalising on us producing content for them free of charge, and most of the time not giving us the opportunity to work for them once the internship is over.”

Ashlea says she’s relieved that she has now secured a paid job, as she and her partner own a house together and have lots of financial responsibilities, so working for free in the hope of furthering her career isn’t an option.

“I feel like something needs to change, but I am unsure what. Perhaps organising some pay system for students interning could make the experience easier for students already struggling financially.

“However, this could result in organisations having a high traffic flow of interns coming in and out of their company.”

It cannot be disputed that unpaid internships have merit; they are a nice way to pad out a portfolio and maybe get a reference for your resume.

But it also cannot be sugarcoated that a lack of mentoring and helpful feedback means unpaid internship programs are only serving the companies.

As unpaid internships continue to become a necessary route to success, the further the socio-economic gap widens in professions that require an extensive number of unpaid hours.

Free labour has become a prerequisite for securing entry-level employment, and some young Australians are being robbed of opportunities purely because the more privileged have the financial stability to undertake free work.

It is time for not only our governments and legal systems to implement change, but for society to change the conversation to find a working system that better supports young Australians.

* name changed for anonymity