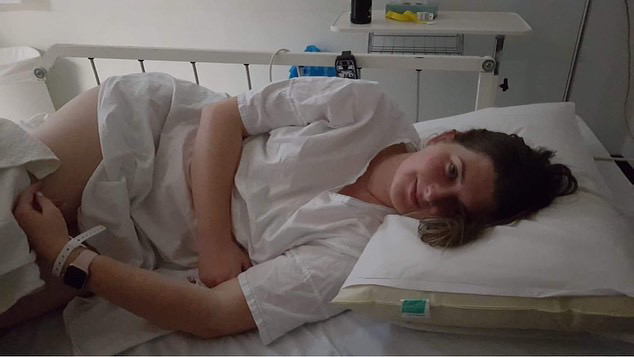

“The fear of being told that nothing is wrong, really stopped me from wanting to investigate further.” OTR Journalist Amelia Walters sat down with endometriosis sufferer Rachael Lahey to discuss her experience with the disease and the importance of Endometriosis Awareness Month. (Image: Amelia Walters)

By Amelia Walters | @ameliawclaire

Rachael Lahey was called a hypochondriac by her family. A worry wart. An over thinker. “Everyone goes through this, you’re not worse off than anyone else,” they told her. Little did they know Rachael was experiencing pain so severe it would eventually hospitalise her.

Nausea, headaches, pelvic pain, back aches and nerve spasms were just some of Rachael’s symptoms. What she was told was an overreaction, was in fact a serious case of what doctors now believe to be stage three endometriosis.

Endometriosis affects one in nine people assigned female at birth in Australia, and approximately 200 million worldwide.

Defined as a chronic illness, endometriosis occurs when tissue similar to what lines the uterus is found in other parts of the body.

It is most commonly found on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, peritoneum (the membrane lining the abdominal and pelvic cavities) and the outside of the uterus, but it can be found in every major organ.

According to the national health advice service, Health Direct, endometriosis is an invisible disease, meaning it is extremely hard to treat and can only be diagnosed by a surgical intervention called confirmation surgery.

Confirmation surgery involves a laparoscopy where a small telescope is inserted into the abdomen to identify endometriosis. A biopsy of the tissue is then taken to laboratory for further testing.

The cursed word: Dysmenorrhea

“If I went to hospital five times, four of those would be a doctor saying ‘it’s just period pain. Here, have some Panadol and Nurofen’, and then I would be sent home,” Rachael says.

“When I was in my early twenties, I would see the term ‘dysmenorrhea’ on my discharge paper all the time and think, what the f**k is this?”

For women who have not had confirmation surgery, they will most likely be met with the word ‘dysmenorrhea’ on their medical, or hospital discharge papers.

“I googled it and soon discovered it’s just the medical term for period pain. I sat there stunned, thinking to myself ‘I’m not here for just period pain,’” she says.

As Rachael explains, the phrase undermines and devalues a patient’s pain levels, thus dismissing the potential underlying issue of endometriosis.

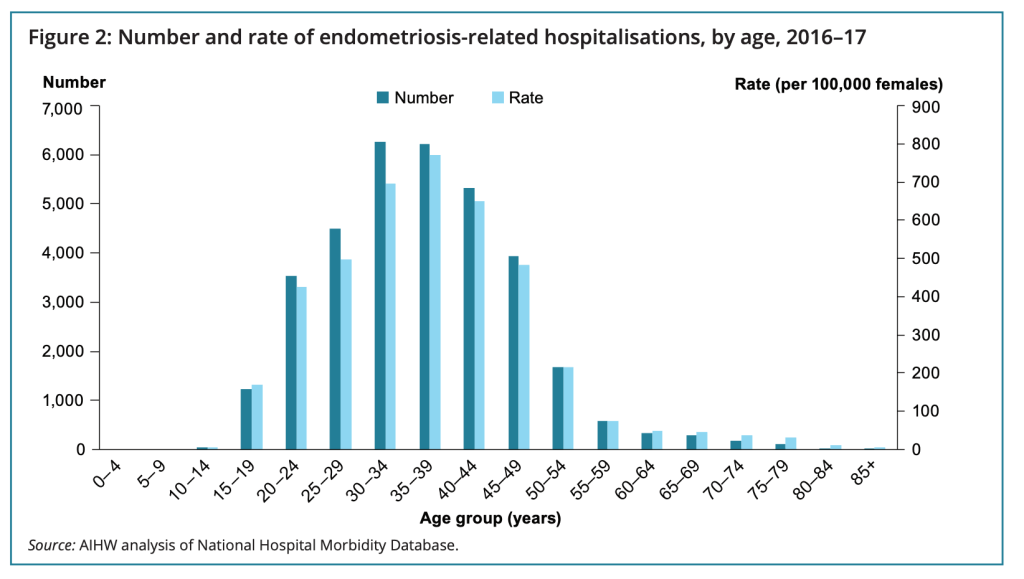

From 2016 to 2017, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) found that approximately six out of every 1000 females in Australia were hospitalised with endometriosis.

However, with one in nine Australian women experiencing endometriosis, this data suggests that cases of the disease are going undetected, potentially due to misdiagnosed dysmenorrhea.

“One gynaecologist I saw, when I told them of my experience, said ‘only 10 per cent of the population struggle with endometriosis, and let’s be honest, you probably don’t,’’’ Rachael says.

Female doctors understand our pain … right?

Sadly, Rachael’s experience is common. Australian radio and television presenter, journalist, health activist and author of ‘How to endo’, Bridget Hustwaite, explains in an interview with The Project, that it is female doctors who most often undermine their patients.

“For me, it took 12 years to get my endometriosis diagnosis, and the Australian average is six and a half years,” Bridget says.

“One year before my surgery, I had a female gynaecologist say to me ‘you don’t have endometriosis, and others have it way worse than you.’ That was shocking, especially coming from a recommended female GP.”

This narrative is far too common among the Australian population, with most women left feeling disregarded.

For Rachael, despite eight years of waiting, and ticking every medical box to indicate she has stage three endometriosis, she is still awaiting confirmation surgery.

“It is the fear of being told that nothing is wrong that really stopped me from wanting to investigate further,” Rachael says.

The investigative process Rachael references is, understandably, one many fear, as it is an expensive and invasive ordeal for most women.

According to Endometriosis Australia, it costs approximately $30,000 per endometriosis patient annually.

For perspective, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reports the average female in South Australia earns around $75,000 per year.

With the deduction of endometriosis care management, this reduces someone’s income to $45,000 — just above the Australian minimum wage.

So, what is the Government doing to financially help those affected by endometriosis?

Thankfully, on March 22 2023, the Albanese Government announced a $58.3 million package for 20 endometriosis and pelvic pain clinics nationwide.

The clinics will provide expert, multidisciplinary services and will each receive more than $700,000 over four years towards hiring specialised staff, investing in equipment, as well as training and development resources.

These clinics will be added to existing general practices around Australia, with the South Australian branch located in Kadina.

With only one clinic announced in South Australia, Rachael says she is hopeful, but knows there is a long way to go.

“It’ll be really interesting to see how this develops and what kind of access this will provide for people suffering with endo, and trying to seek diagnosis,” Rachael says.

“One clinic in SA does not feel sufficient, but it’s great to see that the money is being committed to increasing the services available.

“Hopefully it leads to decreased diagnosis timeframes.”

Has Australia seen an increase in endometriosis education in recent years?

In the updated Endometriosis Progress Report 2023, it was reported that since 2020, $8.57 million was put towards the education and awareness of endometriosis around Australia.

Of this funding, $140,000 was assigned to the Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia to support delivery of the Periods, Pain and Endometriosis Program (PPEP).

The program reached over 80 South Australian high schools, educating students about unusual menstruation symptoms and support services available to them.

Ninety-one per cent of students reported that the PPEP taught them things about their bodies they didn’t know.

Rachael believes programs like the PPEP are a great way to introduce children to the concept of painful menstruation – something she didn’t have the luxury of being educated on in school.

“I don’t remember female sexual education being brought up much in school, let alone endometriosis. It was very much like ‘here’s the uterus, don’t get pregnant,’” Rachael says.

“These days I’m fine talking about it, but 15 years ago, it was taboo, and not okay to talk about your period with people.”

The Endometriosis Awareness Month message

Something that has stuck with Rachael throughout her medical journey, is the idea that doctors might be experts on the human body, but they’re not experts on your body, and they need to listen to the expert.

“I need to advocate for myself because at the end of the day, no one else is going to,” Rachael says.

As Rachael says, Endometriosis Awareness Month acts as a reminder for medical practitioners to respect their patients and consider why a young woman is confiding in them for support. It is a reminder to researchers that their work is necessary and valued; and a reminder to all women who experience unrelenting pain, that they deserve to be seen and heard.

Rachael wants those affected by endometriosis to know that although the disease is invisible and silent, it does not mean that you should be too.

If you or someone you know is impacted by endometriosis, you may find some of the clinics and organisations below useful: