Yorke Peninsula’s Dhilba Guuranda Innes National Park has been working hard with its Traditional Owners to bring the Yorke Peninsula back to life. OTR journalist Joanna Tucker takes us on a journey to learn about the history of the park, and how a co-management agreement between the Narungga Nations and the State came to fruition. (Image: Joanna Tucker)

By Joanna Tucker | @joannatucker00

Marna Bangarra, meaning healthy or prosperous country in the Narungga language, is a long-term project for reintroducing native species and rewilding the southern part of the Yorke Peninsula. Rewilding is the process of restoring an area to its natural, uncultivated state. This project was responsible for the reintroduction of species in the Dhilba Guuranda Innes National Park in 2021 and has plans to reintroduce even more native species back into their environments for the next 20 years. The Buthera Agreement, named after Buthera’s Rock — a dreamtime story which teaches respect for the land to children — was responsible for drafting the co-agreement for the Dhilba Guuranda Innes National park, making the rewilding of the Yorke Peninsula possible.

Heading to Dhilba Guuranda

The drive from Adelaide to the Dhilba Guuranda Innes National Park on South Australia’s Yorke Peninsula was long and exhausting. Every now and then I caught myself checking my phone. No service. Checked again an hour later, no service. We stopped at Pork Wakefield for fuel, and then later at Minlaton for a snack, with their local bakery providing delicious pastries. As soon as I saw the signs for Marion Bay, I knew we were close.

After ensuring we had paid for our vehicle to enter the park, we headed towards the Cable Bay campground to set up our tent before it got too dark. It had been raining previously, but we were lucky enough to have a campground that was not covered in giant puddles of muddy water. Although, heading towards the long drop in the dark later that night proved to result in wet shoes. We were excited to begin exploring the fascinating land of the park, but we had one goal in mind: to see a brush-tailed bettong.

Brush-tailed bettong

The search for the hidden ecosystem engineer, the brush-tailed bettong, was a long and futile mission. I had been told they performed highly important roles in keeping ecosystems healthy, so perhaps they had their tiny hands full.

Landscape ecologist from the Northern and Yorke Landscape Board, Derek Sandow, said brush-tailed bettongs dig in the soil looking for fungi, tubers, and insects to eat.

“A single brush-tailed bettong can turn over between two and six tonnes of soil per year,” Sandow said.

“This aerates the soil and allows for water penetration, and provides a microhabitat for seeds to establish, promoting a health and diverse ecosystem.”

The brush-tailed bettong was extinct within the Dhilba Guuranda Innes National Park until the Marna Bangarra project was created. Sandow, along with others, is part of this project that works to bring the land back to its original state before colonisation.

“Brush-tailed bettongs were present on the Yorke Peninsula prior to European colonisation, so native plants and ecosystems have evolved over time with their presence … and will benefit from their presence [again],” Sandow said.

With no luck in finding any brush-tailed bettongs at our campsite, we headed towards our first trail.

Gulawulgawi Ngunda Nhagu Lookout

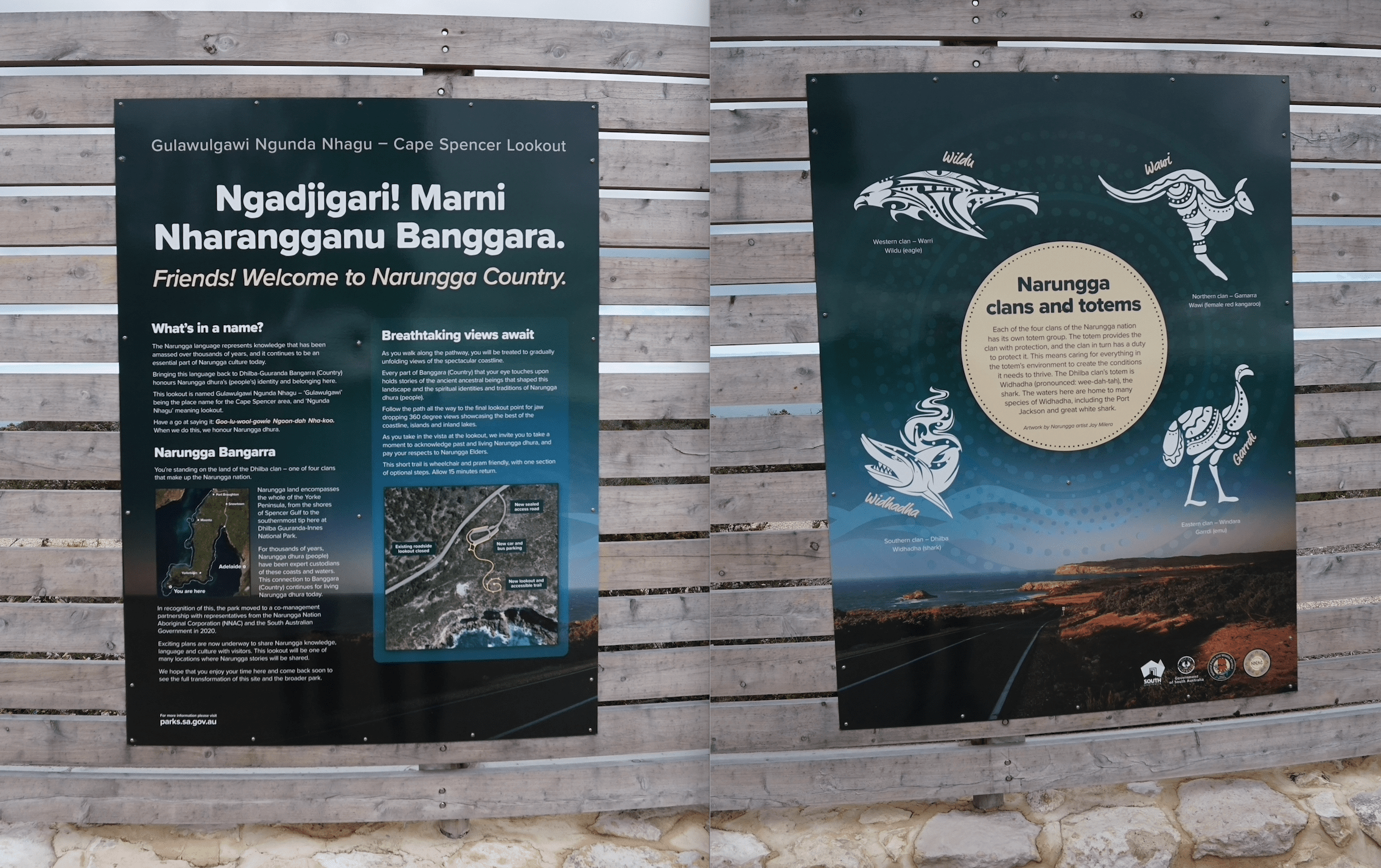

“The co-management only started in 2020?” I asked my partner, out of shock, as we made our way to our first stop within the Dhilba Guuranda Innes National Park: the lookout named Gulawulgawi Ngunda Nhagu. “Gulawulgawi” being the place name for the Cape Spencer area, and “Ngunda Nhagu” meaning “lookout” in Narungga, the Traditional Owners’ language.

This lookout consisted of strategically placed mini lookouts along a winding path, eventually making it up to the highest point of a hill, giving a serene view of three islands. The furthest to the left is Haystack Island, and the two to the right are Seal Island and Althorpe Island. This trail was a great start to my time at Dhilba Guuranda Innes National Park, and even suitable for families. However, it irked me that the co-agreement between the Narungga people had only begun in 2020.

The country of the Narungga people extends as far north as Port Broughton and east to the Hummock Ranges, with their neighbours being the Kaurna of the Adelaide Plains and the Nukunu to the north.

The Narungga people are passionate about their strong cultural and spiritual connection to the country; they believe that, for the land to provide for them, they must care for the land.

The land we were walking on belonged to the Dhilba clan. The Dhilba clan was the southern clan, with the Widhadha (shark) as their totem. I learnt from the Narungga Nations Aboriginal Corporation (NNAC), Garry Goldsmith, that each clan had their own totem which provided the clan with protection. The Narungga people believed that, as their totem protected them, they in turn had to protect their totem. This meant caring for everything within their totem’s environment.

“The four clan groups are North, South, East and West on Guuranda. The Dhilba, Warri, Garnarra Wawi and Windara Garrdi, that are all part of the Narungga Nations,” Goldsmith said.

I wondered how the land must have looked all those 60,000 years ago whilst travelling up the trail, when the Narungga people were looking after the land without disruption.

The formerly known Innes National Park was co-named to Dhilba Guuranda Innes National Park on November 14 2020, as “Dhilba” signifies the clan of the land the park resides on, and “Guuranda” means Yorke Peninsula in Narungga. “This recognises the Southern Narungga people and that it is their country,” Goldsmith said.

The trails were stunning and set my expectations high on what else the park would hold for us. Before entering, we headed to the park information site and asked the front desk where we could find a brush-tailed bettong. The receptionist highlighted on our map where they had been last released, and we were on our way there.

Heading towards the highlighted area on the map, we noticed we were close to the historic Inneston trail. There was nowhere to park, but there was a giant neon-orange sign that read “BETTONGS IN PARK, DRIVE CAREFULLY”, so I knew we were in the right place. Derek Sandow warned us of the care that had to be taken while driving near the bettongs. Unfortunately, we were still unable to get any sightings of the small marsupial.

“We have observed negative human impacts such as speeding on roads through the park, resulting in three brush-tailed bettongs dying from vehicle strikes,” Sandow said.

The history behind Dhilba Guuranda

The Dhilba Guuranda Innes National Park has been functional since 2016. Being the last remaining place that resembles what Guuranda (Yorke Peninsula) used to look like 60,000 years ago, the land is of high significance to the Narungga people.

The State Government called for expression of interest for treaty in 2017, and the Narungga people responded. At the time, Garry Goldsmith was chairperson of the NNAC. Goldsmith and another elder of the Narungga community were lucky enough to be successful with two other groups who were interested in discussing treaty.

Goldsmith also said that the State Government was not willing to discuss the five key components to a treaty: compensation, recompense, resource sharing, governance, and sovereignty. Nonetheless, the Narungga people, as a nation, wanted to find out if they could explore something like a treaty, and were successful. This resulted in an agreement between Narungga Nations and the State: The Buthera Agreement.

“Buthera is a dreaming story of ours, who is a giant Narungga man who is a protector of our people … We thought that was a good way to start a foundation story,” he said.

“National parks are co-managed under a native title agreement … we didn’t have a native title yet, but the Department of Environment and Water said, ‘we will give that to you under [the Buthera] agreement’.”

This was historic for Australia. The Buthera Agreement was the first of its kind. Typically, a national park is co-managed under a native title agreement. This agreement was not officially granting native title to the Narungga Nation but was granting native title through co-management of the Dhilba Guuranda Innes National Park.

Native title is given if a group can prove they have culture through sites, language, practices, and can agree on where their boundary with other nations is.

“It showed the State Government was willing to step outside of normal acts for the Narungga people,” Goldsmith said.

The Marna Bangarra project

The Marna Bangarra project originates from the Narungga dialect. “Marna” means “healthy or prosperous” and “Bangarra” means “country.” This name was chosen to honour the Yorke Peninsula’s Traditional Custodians: the Narungga people. This project would have been impossible without the efforts of the NNAC and the South Australian Government to protect the traditional land of the Narungga people.

“So far, 120 brush-tailed bettongs have been reintroduced; 40 from Wedge Island in August of 2021; 36 from Western Australia in June of 2022; and another 44 from Wedge Island in July of 2022,” Sandow said.

Wedge Island, located in the Spencer Gulf, is a source of protected brush-tailed bettongs because the island is completely fox and cat free — predators of the brush-tailed bettong. Walking through the historic fishing village, you will get to the view (pictured above) and be able to see Wedge Island on the horizon.

“Although it is in the early days, progress has been very good thus far, with animals showing signs of good health, breeding, high levels of survivorship, dispersal from release sites, and lots of evidence of digging and foraging,” Sandow said.

The other species involved include the Southern Brown Bandicoot, Red-tailed Phascogale and the Western Quoll.

“The reintroduction of the brush-tailed bettong is a significant step for improving the health of the country, which is an important part of the aspirations of the Narungga traditional owners.”

Is it possible to be respectful while enjoying your holiday?

Derek Sandow has also witnessed humans accessing areas of the park that they should not by driving, walking, and biking off designated tracks and trails. Nonetheless, he still believes that it is important for the public to be able visit and enjoy the park, staying at the park numerous times himself. I even witnessed rule-breakers myself, with a couple bringing their dog into the park, which is a predator of the brush-tailed bettong and disrupts the native flora.

We also visited Cape Spencer and walked the Cape Spencer Lighthouse trail just before sundown and were lucky to witness the most idyllic views as the sun was setting over the cloud-filled sky, lining our view with purple and blue pastels.

Even as the sun went down, we had still not seen a brush-tailed bettong. But we had seen the effects of the Marna Bangarra project, with wild flora and fauna blossoming even as the weather got colder. The array of opportunities within the environment beginning to form are nothing compared to what the Narungga people used to be able to sustain — hence their longevity, being the oldest living culture in the world.

“What we’re trying to do through these projects for the Narungga is to bring back the acknowledgment and recognition that this always was, and always will be, Narungga land,” Goldsmith said.