Because Adelaide no longer has a paediatric cardiac surgery unit, SA patients have to travel interstate for care. OTR journalist Seth Crothers reports on the real-world impacts this restriction has had on families, and what is being done to fix it. (Image supplied: Bella Ward)

By Seth Crothers | @seth_crothers

“Imagine having a brand-new baby, and that baby being ripped away from you to go to another state while you’re at home. Some people aren’t in really good paying jobs, and they can’t fund it, so they have to go without their babies for however long it takes.” – Whyalla mother Bella Ward

Faced with decades of uncertainty about the health of their children and long waiting times for interstate transfers, South Australian families and industry specialists are crying out for the establishment of a paediatric cardiac surgery unit in Adelaide.

According to the ‘Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’, around nine in every 1,000 babies are born with congenital heart disease. Tenaya Ward is one of them.

At just seven days old, Tenaya was flown to the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) in Melbourne after a prenatal diagnosis of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. This is a complex malformation where the atria, the heart’s two upper chambers, are oppositely connected with the ventricles, the heart’s two lower chambers. Specialists placed a band around Tenaya’s artery, training the ventricle for the arterial switch operation, a procedure to reconnect the arteries and ventricles correctly.

According to the Women’s and Children’s Hospital Alliance (WCHA), an independent community campaign of current and former clinicians, Adelaide sends about 100 babies to Melbourne each year for lifesaving cardiac surgery.

At just 20 weeks’ gestation, Tenaya’s mother Bella Ward was at her routine pregnancy scan in Adelaide when her paediatrician told her to abort her baby. “She said, ‘Just get rid of your baby’,” Ward says.

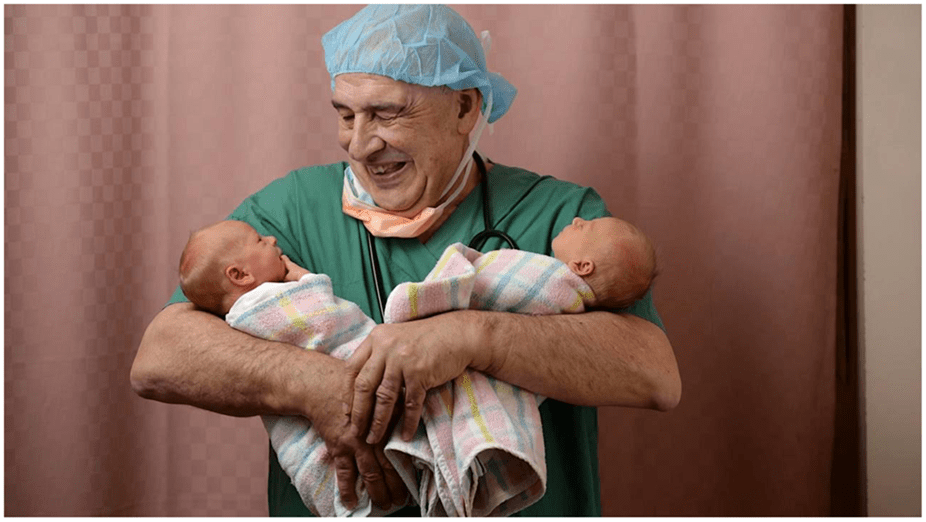

Seeking a second opinion, Ward and her husband Mark Ward met with a paediatric cardiologist from the Women’s and Children’s Hospital (WCH) who told them abortion was not an option. Ward described the cardiologist as “the most beautiful man we had ever met”.

Tenaya was also diagnosed with a secondary heart block – intermittent electrical signals in the heart’s upper and lower chambers – during Ward’s scan at 20 weeks’ gestation. In April 2020, Tenaya was born with a heart rate of 40 beats per minute instead of 160 beats per minute, the typical heart rate of a newborn.

Two years after Tenaya’s birth and her first successful procedure to train the ventricle, she underwent a two-day arterial switch operation. This operation took place on Bella and Mark Ward’s March 2022 wedding anniversary.

Six months later, Tenaya was taken back to Melbourne because she had begun occasionally turning blue and sweating profusely.

Specialists identified that Tenaya’s heart was still not beating in a coordinated manner. Her condition was discussed by general surgeons and specialists from RCH and around the world. They decided the most suitable option was to implant a pacemaker. Other alternatives included a ventricular assisted device (VAD), which assists the heart to pump blood to the body from the heart’s lower chambers, or a heart transplant.

Ward says after the pacemaker was implanted Tenaya “sprung back”. “She was beautiful. She was eating. She was happy,” she says.

The family – Tenaya’s mother, father and grandmother – has been living on a Melbourne roster so Tenaya could be regularly monitored. Just before Christmas in 2022, Tenaya underwent a routine blood test under general anaesthetic when her heart stopped beating for six minutes.

Tenaya’s grandmother called her daughter with the terrible news. Ward went into their bedroom to tell her husband who was sleeping. “My husband was on nightshift, so I walked in to tell him and that’s when it hit me, because I had to say the words to him,” she says. Bella Ward wouldn’t hear from doctors for another hour.

“When mum took her in for that [blood test], she’s like, ‘[Tenaya] called out for Nanny, and then her eyes rolled back.’ That’s when it all happened — as soon as mum walked out the door.”

Following her resuscitation and slow recovery in early 2023, specialists decided to insert a VAD machine, a procedure never before conducted on a child with Tenaya’s condition. Two surgeons conducted the cardiopulmonary bypass procedure to insert the VAD machine which pumps blood from the heart to the rest of the body. The procedure was successful.

Ward saw her daughter happy again. While the outcome was good for Tenaya, other South Australian children requiring heart surgery have not been so fortunate.

South Australia’s paediatric cardiac deaths

On October 20, 2020, obstetrician-gynaecologist and former convenor of the WCHA, Professor John Svigos appeared before a South Australian Parliamentary Committee reviewing the state’s health services. He reported that, in the past month, ‘three South Australian babies with major cardiac diseases had died.’

Following Professor Svigos’ evidence, South Australian Salaried Medial Officers Association chief industrial officer, Bernadette Mulholland informed committee members of another paediatric cardiac death within the week leading up to the hearing. One of the four infants died from a rare heart abnormality affecting one in 100,000 babies.

Committee chair MLC Connie Bonaros described the deaths as “unacceptable”, “reprehensible” and “disgusting”. Following the hearing, SA Health’s chief medical officer Dr Michael Cusack ordered an investigation into the deaths titled, Review of Four Neonatal Deaths at Adelaide Women’s and Children’s Hospital, led by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care.

Professor Svigos advised the committee of another “two near misses” recorded at the WCH in early 2021.

In an interview, he says following the deaths and the investigation, South Australia took action to acquire a freestanding Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Machine (ECMO). An ECMO pumps and oxygenates blood externally, allowing the heart and lungs to rest for patients at risk of death.

According to the investigation report, ECMO was suitable for one of the babies who died, but the device, located interstate, arrived in Adelaide the morning after the baby died.

“What they’re saying is, ‘We might be able to get a bit of an ECMO to keep things going but if a child gets into difficulty, were not going to be able to help it’,” Professor Svigos says.

The investigation found the implementation of high-risk delivery policies and practices – briefings, clinical staff presence and transfers – was unsatisfactory and must be improved. “Despite sophisticated state-based retrieval services able to transfer rural patients to the city,” the investigation reported, “inter-state retrieval presents a challenge”.

It made recommendations to improve communication between interstate hospitals and specialists, as well as the implementation of national transfer protocols. This aims for better coordination and clearer roles and responsibilities of all staff. It did not recommend the establishment of a paediatric cardiac surgery unit in Adelaide.

Professor Svigos is critical of the recommendations. “We’re half giving [South Australia] a paediatric cardiac unit. Be happy with that,” he says.

In May 2019, more than a year before the death of the four babies, working clinicians and administrators from the Women’s and Children’s Health Network (WCHN) released the Cardiac Surgery Business Case (which is not publicly available, but which OTR has seen). The case proposed the establishment of a paediatric cardiac surgery unit in Adelaide.

It highlighted the dangers of operating a freestanding ECMO without a fully established unit and highly trained specialists. For example, if the unit’s external connection to a patient fails, paediatric cardiac surgeons must connect the machine internally.

South Australia employs one adult cardiac surgeon who is paediatrically trained, but due to a lack of time, facilities and equipment, “only low complexity closed procedures have been performed [in South Australia], in small numbers”.

So, is a paediatric cardiac unit based in Adelaide a viable proposition?

A paediatric cardiac unit could be feasible in Adelaide, but will the numbers be a problem?

Seventeen years after the 2002 termination of a paediatric cardiac surgery at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital in South Australia, the business case emphasised that its closure had “greatly exacerbated the strain placed upon already stressed families by requiring their relocation interstate, at times for many months”.

Clinician authors of the business case say restoring a similar service, “will not only put a permanent end to this financial drain, it will generate substantial local income.”

The earlier unit, established in 1994, performed surgery but, according to the business case, discontinued following a significant reduction in “numbers of children requiring open heart surgery to the point where the numbers of cases eligible for this type of surgery in South Australia was too small to justify”.

The case explains that the re-establishment of a paediatric cardiac surgery unit in Adelaide would cost an estimated $6 million, and $1 million each year to maintain.

The business case also reports that South Australia spends $5 million each year to transfer paediatric cardiac patients interstate, predominantly to Melbourne. Since the closure of the unit at the WCH in 2002, the state has spent up to $90 million relocating patients interstate for treatment. Business case clinicians say inaction will “perpetuate the current risks”, and the “financial, clinical and social benefits greatly outweigh those of the current service”.

In mid-2020, the WCH chief executive and board released the SA Paediatric Cardiac Surgery Services Review to review the business case.The review drew attention to guidelines set by national and international governing bodies, including the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. It identified minimum surgical procedure ratios per surgeon, noting a link between high mortality and low surgical volumes.

The review recommends a minimum of 200 to 300 paediatric cardiac surgeries per year, consistent with international standards. It argues there would unlikely be sufficient operations in Adelaide to ensure surgical safety.

Professor Svigos disagrees. “If [the Women’s and Children’s Health Network is] just knocking us back because of numbers …, I think numbers are a very unreasonable view to take,” he says.

They can come from other places without a paediatric cardiac unit. Northern Territory infants are waiting for cardiac surgery in Brisbane, Sydney, Perth and Melbourne. They could contribute to Adelaide’s surgical numbers.

Infants needing operations could also come from overseas. The East Timor Hearts Fund, Australia’s only NGO dedicated to providing life-saving heart surgery, education, prevention and research projects, could add to South Australia’s surgical numbers. Professor Svigos says the East Timor fund has administrative connections in Adelaide. “They would like to do it in Adelaide, it would be very convenient for them.”

He says between 30 and 50 privately funded south-east Asian children could come to Adelaide each year, at no cost to the state’s health system. “How can you justify leaving children in south-east Asia high and dry when we could provide them with this service?”

With opportunities to create sufficient surgical volumes from the Northern Territory, the East Timor Hearts Fund and South Australia’s new and pre-existing patients, a facility for paediatric cardiac surgery would meet surgical number requirements equivalent to Perth.

The future is now, but will a new facility help families and children experiencing ongoing adversity?

Bella Ward is caring for Tenaya at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne. She says many things would be different if Tenaya had received care in Adelaide. There would have been much less hardship for the family.

“We wouldn’t be in a financial struggle,” she says. “We wouldn’t be separated. If we wanted to be with her, we could be with her … and still go to work.”

The cost of taking sick infants to the place they can be treated is only partly covered. In South Australia, families are supported by SA Health’s Patient Assistance Transport Scheme (PATS), a subsidy program for South Australians requiring specialist intrastate or interstate medical attention.

Despite Ward’s appreciation for the scheme, she says the funding is insufficient when travelling interstate regularly.

“PATS is great, but they don’t cover a lot,” she says. “I might be lucky to get three or four hundred dollars back. Before we leave Whyalla … we could be spending a minimum of $2,000 and I haven’t even walked out the front door,” she says.

Mark Brooke was CEO of HeartKids, an organisation supporting children with congenital heart disease. When the business case was released, Brooke declared his “wholehearted” support for a re-established unit in Adelaide. He emphasised, in a letter to the WCHN, which OTR has seen, HeartKids’ first-hand experience with the pressures upon families, including the “severe financial stress”, of interstate travel.

Brooke says HeartKids received an average of 100 to 150 referrals annually from the WCH, Darwin Hospital and regional hospitals for families requiring financial assistance.

But, in late 2022, there is a glimmer of hope.

In November 2022, ‘legislation to build Adelaide’s new Women’s and Children’s Hospital passed through South Australian Parliament.’ The new hospital is planned to be 25 per cent larger than the current Women’s and Children’s Hospital and is due for completion in 2031. The new hospital website says the facility will integrate “future proofing for cardiac surgery”.

Professor Svigos supports this. He says South Australia’s Minister for Health, Chris Picton, has indicated there is room available to establish a paediatric cardiac surgery unit in the new Women’s and Children’s Hospital. During a press conference to announce the new site of the Women’s and Children’s hospital in September 2022, the Minister spoke of the need for additional services, “such as cardiac surgery, which [the SA Labor Government] wants to future proof right from day one”.

To ensure any unit is operational when the hospital opens, Professor Svigos says South Australia must begin recruiting specialists to the facility now. “In order to run a cardiac surgery unit, you have to have well-prepared staff,” he says. “It’s like anything, if you say to [surgeons], ‘We’re going to offer you a state-of-the-art unit … you’ll have the chance to decide how you want to set up the new unit’. That’s very appealing.”

‘During the 2020 parliamentary hearing’, Professor Svigos argued that if we accept the current standard, “we’re not really doing much better than a lot of other places”. “We’re supposed to be state of the art … and yet we send away sick babies to another state to get them fixed,” he says. “That’s an indictment on us, really.”

Director of Cardiology at Adelaide’s Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Professor John Horowitz, agrees. He also focuses on research. “The Women’s and Children’s Hospital Cardiology Unit has never reached an international standard with its research,” he says. “Really good surgeons are usually most comfortable working in a ground-breaking academic environment.”

Although many families are supportive of the unit’s establishment, Stuart Martin, whose son has congenital heart disease, remains undecided. Josh Martin endured six open-heart surgeries in Melbourne after a 19-week prenatal scan revealed he was suffering from irregular blood flow in the heart.

After the diagnosis of a narrow left pulmonary artery, a blood vessel that connects the heart and lungs, and no connection between the right pulmonary artery and the heart’s right lower chamber, Stuart Martin says he “can’t speak highly enough of the team [in Adelaide] and in Melbourne”.

“I don’t envy anyone having to make that choice between Adelaide and Melbourne … because the Melbourne experience for us has generally been pretty good.”

Although grateful for Josh’s treatment, Martin reminisces about how much easier life could have been if Josh had been operated on in Adelaide. He speaks of “having access to familiar territory”.

But he’s also concerned about quality and safety. “We’d rather have a surgical team that is doing this every day,” he says. “Because they’re doing it all the time and that’s solely their purpose … there is a level of reassurance.”

Professor Svigos remains steadfast in his pursuit of change. “If we don’t do something about the issue now, children will continue being sent to Melbourne for the next 30 years.”

SA Health the Health Minister were given an opportunity for comment but they declined.