ADHD is often perceived as being a condition that both begins and ends in childhood, but this is not the case. In ADHD Awareness Month, OTR Editor Anna Ngov reports on the realities and challenges of late-life diagnosis. (Image: Anna Ngov)

By Anna Ngov | @annangov

Rachel Crees, a program manager in education, was 44 years old when she was first diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Defined as a chronic neurodevelopmental condition, ADHD is commonly characterised by “difficulties with concentration, attention and impulse control”.

Crees’s official diagnosis came after 20 years of trying different medications for depression and anxiety, a time during which she found that none of them were quite working effectively.

“I was going back to my GP for yet another prescription of the same antidepressant and thought, ‘Am I treating the right thing here?’,” Crees says.

This doubt prompted Crees to do her own research into whether or not there was an underlying issue and have a discussion with her GP about the evidence she had found – evidence that pointed towards having ADHD.

When she first raised the possibility of having ADHD with her GP, she was met with an open discussion and given a referral to a psychiatrist, but Crees says this is not always the case for people seeking a diagnosis.

“What you often hear is people go to their GP saying, ‘I’d like to explore whether I’ve got ADHD’ and the GP just goes, ‘No, it’s not. It’s anxiety, it’s depression, it’s whatever’,” she says.

“I was fortunate that my GP went, ‘Sure, let’s look into this.’”

After being diagnosed with ADHD by a psychiatrist a year and a half ago, Crees found that there was a lack of local information about adulthood ADHD, which propelled her to create the ‘Adelaide Adult ADHD’ website.

“I really couldn’t find anything that made me feel like I could be better informed about ADHD as an adult, as a woman, and in South Australia,” she says.

“Then I set that website up and I thought, ‘Well, if I’m doing this, then I bet there’s other people who are too, so I’ll just set this up and maybe that’ll be some sort of help.’

“[The website] is just a place to go to realise that you’re not alone – that’s all that it was set up to do.”

Not just “a seven-year-old boy bouncing off the classroom walls”

While it is estimated that about 2.5 to 5 per cent of Australian adults have ADHD, there is often still the misconception that the condition only presents itself in childhood.

“When you think about it, it’s horribly illogical that you’d think you could diagnose a child with something, 30 years ago, and expect there to be no adults with that,” Crees says.

“What happened to those children? Did they fall off the face of the earth?

“You don’t grow out of it.”

For 40-year-old Claire May*, who had been seeking strategies to help with executive functioning tasks, the stereotypical perception of ADHD only being a childhood condition meant the idea of having it as an adult had never crossed her mind.

“[ADHD] was never addressed as a thing with my psychologist,” May says.

“A friend of mine in Melbourne, she was diagnosed, and she said, ‘You have to go! You totally have ADHD too! You need to investigate this!’

“I thought at the time, ‘Oh, that’s a bit much, I don’t know. I’m not a seven-year-old boy bouncing off the classroom walls, throwing chairs, and drinking red cordial.’

“I felt like [those are] the things I would have needed to be exhibiting to be diagnosed with ADHD.”

After taking her friend’s advice, doing research online, and finding information that correlated with her own life experience, the mother-of-two initiated the process of seeing a psychiatrist, which led to her being diagnosed with ADHD over the last six months.

Social media and increased recognition

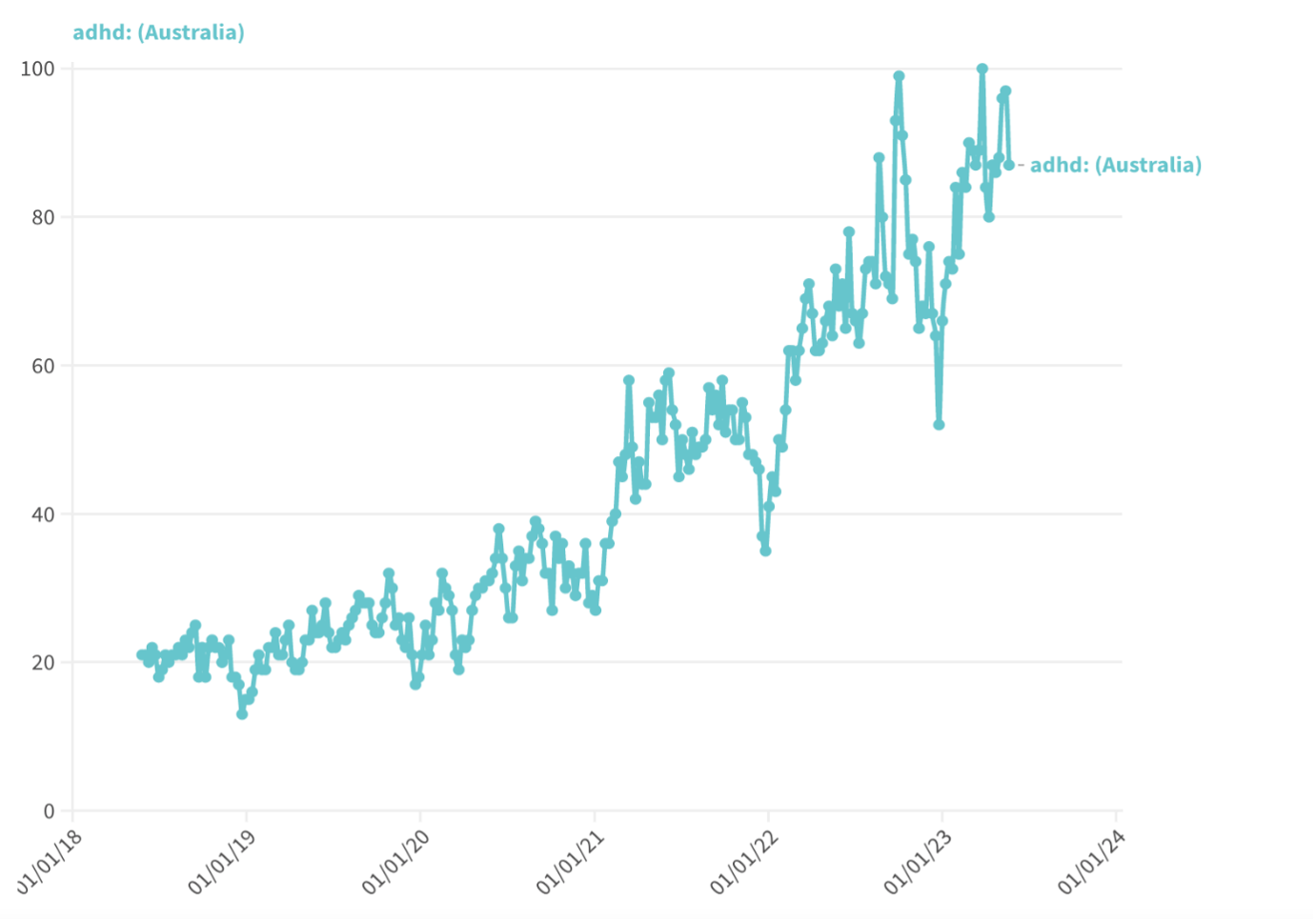

Crees and May are just two of a growing number of adults who have been diagnosed in Australia in recent years – a time which has also seen an increased demand for ADHD assessment, diagnosis and treatment, and a steady increase in ADHD-related searches.

President of the Australian ADHD Professional Association (AADPA), Professor David Coghill, says the increasing number of adults seeking ADHD diagnosis is simply due to the overall “increased recognition within society”.

Coghill, who has been in Australia for seven years, says this increased recognition can, in part, be attributed to the more positive coverage in the media.

“When I first came to Australia, the media coverage of ADHD, for example, was often very negative,” Coghill says.

“Now, what we’re seeing, is a much more positive and supportive coverage from the media.

“There’s also a change in the way that social media is dealing with ADHD and is talking about ADHD.

“Young people, in particular, are being exposed much more to the idea about ADHD.”

For 32-year-old Stephanie English, a formal ADHD diagnosis finally came last year after she first suspected she had the condition in high school.

“When I was about 16, I said to my parents and my GP, ‘I think I’ve got ADHD’,” English says.

English’s parents, both of whom are teachers, turned down the idea as she was not displaying the symptoms typically recognised at the time.

“[My parents said], ‘No, no, you’re not hyperactive, you’re not bouncing off the walls, you don’t have that.’”

Fourteen years later – after being diagnosed with depression instead and finding her medication was not alleviating her symptoms – English says it was social media that encouraged her to revisit the possibility of having ADHD.

“I started looking at TikTok, and thought, ‘Oh, maybe. Maybe this is it’,” she says.

“[Having] social media has helped spread awareness, where people go, ‘Oh, I might identify with that’, and then do their own research.

“It’s definitely not a main source of information, but it is very helpful.”

Professor Coghill, who is also the Chair of Developmental Mental Health at the University of Melbourne, agrees that while social media coverage of ADHD can be positive, it is vital for adults to seek a formal diagnosis from a qualified healthcare professional.

“Sometimes, people can be influenced by what they’ve seen on social media, without actually taking a really objective view of what ADHD is,” he says.

“In order to get treatment for ADHD, you still need to be diagnosed by a professional.”

Barriers to a formal ADHD diagnosis and medication access

The process of obtaining a formal ADHD diagnosis is often fraught with difficulties, as the condition can only be diagnosed by a clinical psychiatrist, and many adults encounter barriers to seeking diagnosis and access to treatment.

One of the main barriers in the diagnostic process, Coghill says, is actually finding a clinical professional who will carry out the diagnosis.

“Even though there’s an increased recognition [of ADHD], there are still huge problems with accessing services,” he says.

“People are having to wait for many months, sometimes years, to access services.”

After receiving a referral for an ADHD assessment in 2021, English waited nearly a year for an appointment with a private psychiatrist.

“Trying to a find a psychiatrist whose books were open, who would see me, took me about eight to 10 months,” she says.

“It was just me ringing people and them going, ‘No, don’t have anything.’”

Akkadian Health is one mental health service that provides people with access to clinical professionals in the field.

Akkadian Health clinical director and senior consultant psychiatrist, Doctor Jörg Strobel, says there is a significant demand for adult ADHD assessments, and many psychiatrists exclude them from their services.

“Of [approximately] 350 psychiatrists in South Australia, I know of less than 10 who would regularly see people [who think they have] ADHD,” Strobel says.

“We have booked out all available times for about four months and still have referrals flooding in daily.”

Professor Coghill says the limited availability of psychiatrists is also due to the large number of patients entering the private health system.

“Public mental health services are still not funded, or geared up, to doing ADHD assessments,” he says.

“So, most people are having to go through the private system, [which] is not only limited in capacity, but also people are limited in their ability to pay.”

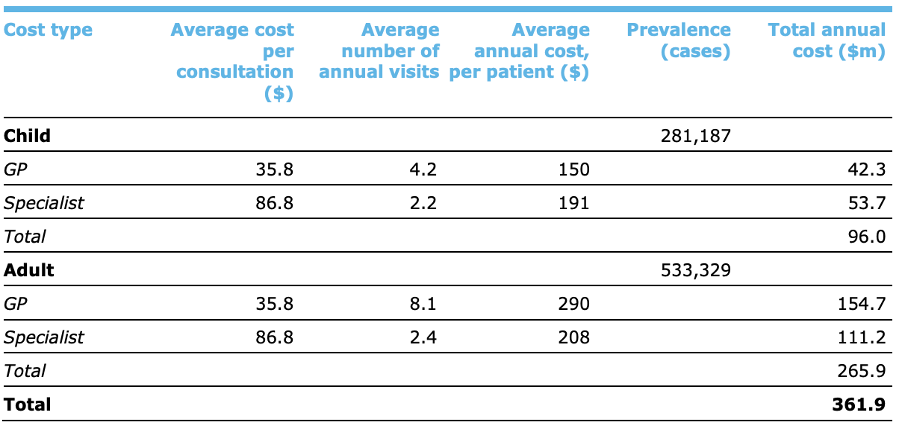

According to data published by Deloitte Access Economics in its 2019 ‘The social and economic costs of ADHD’ report, which was prepared for AADPA, the total annual out-of-hospital health costs for adults with ADHD is estimated to be $361.9 million in Australia.

The data was produced, through a bottom-up approach, by estimating the number of cases incurring each cost item and multiplying the number of cases by each item’s average cost.

While the out-of-hospital costs were estimated for GPs and specialists (including psychologists), no suitable data on the costs of other allied health services, such as private psychiatrists, were identified for inclusion in the report due to data limitations.

However, increased costs can indeed be attributed to these other allied health services, with Crees noting a considerable cost alone in seeking a psychiatrist for an initial diagnosis.

“I assumed, like a referral to any specialist, it would be worst case $200 and I might get $50 to $100 back on Medicare,” she says.

“It was $600 for one appointment.”

Following a formal ADHD assessment from a psychiatrist, during which time recommendations can be made regarding medication and treatment, patients are then required to return to their GP so they can prescribe the medication – a process that incurs additional difficulties.

Doctor Strobel, who has 30 years of clinical experience, says a challenging part of accessing ADHD treatment directly relates to the nature of the medications used to stimulate the activity of certain chemicals in the brain.

“The treatments, mainly Ritalin and Dexamphetamine, are ‘schedule 8 drugs’ and are subject to specific regulation and controls,” Strobel says.

Schedule 8 drugs, also known as drugs of dependence, are prescription medicines that, despite having legitimate therapeutic uses, have a greater risk of misuse, abuse, and dependence.

This in itself can be a barrier to people seeking access to treatment, with English and Crees finding that some doctors are hesitant to prescribe a drug of dependence.

“I found there were a couple of GPs that didn’t want to prescribe me the medication,” English, who did eventually get access to medication, says.

“Some GPs go, “Look, I know I’ve got this referral. I know the psychiatrist told me that I should give it to you, but I’m not prepared to. It’s too big a risk,’” Crees says.

The stimulant dose is then commonly titrated according to the response of the patient, which Crees believes adds on to what is an already “massively difficult process”.

“This means multiple trips back to the GP, more time, more money, and more mental load,” she says.

“It probably took me a year from when I first said to the GP, ‘I’d like to explore this’, to when I was on a sustainable dose of medication.”

There are two types of stimulant medications for ADHD, known as short-acting and long-acting forms, which each differ in the way they come into effect inside the body.

Under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), the majority of people with ADHD will generally begin treatment with short-acting stimulants, with the PBS subsidizing these more than long-acting forms.

For May, who is also a coeliac, navigating the medication pathway for treatment was particularly difficult due to the gluten content in short-acting medications.

“I had to try and get gluten-free short-acting compounded in South Australia,” she says.

“I went to one chemist and then I rang three compounding pharmacies, but none of them could do it because of the restricted ingredients,” she says.

“Then they could, but it was going to be $3,000 for a month’s supply.”

May eventually returned to her psychiatrist to be prescribed for long-acting medication, but describes the entire process as “unnecessarily complicated”.

What is currently being done to aid the diagnostic process?

In 2022, AADPA published the ‘Australian Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for ADHD’.

The 215-page Guideline provides a summary of scientific evidence and recommendations for the identification, diagnosis, support, and treatment for people with ADHD.

Professor Coghill says the AADPA guidelines, which were a collaboration between clinical professionals, researchers, and people with lived experiences with the condition, followed “rigorous evidence-based processes”.

“The National Health and Medical Research Council have a protocol by which one develops evidence-based clinical guidelines,” he says.

“The Guideline development group followed those processes very rigorously.

“They searched the available evidence, they drew recommendations based on that evidence, and where there wasn’t enough robust evidence, the Guideline group made consensus decisions.”

The Australian Government provided $1.5 million to AADPA to develop the Guideline, with the Minister for Health and Aged Care, Mark Butler, heralding the Guideline as an important tool for informing medical and allied health professionals.

“This Guideline sets the benchmark for the best-practice evidence-based assessment, treatment and support for people living with ADHD, and also lays a roadmap for ADHD clinical practice, research and policy,” Butler says.

On March 28, 2023, the national Senate referred a new inquiry into the barriers to seeking assessment, diagnosis and support for ADHD, and access to medication and treatment.

While originally due to report by September 27, the Assessment and Support Services for People with ADHD Inquiry has now been granted an extension until November 6.

Coghill also made a submission to the inquiry, saying, “we need to do better”.

“Hopefully, the government will see the [inquiry] as an opportunity to increase the funding that goes towards ADHD and look at ways of increasing how people access care.

“I’m hopeful that the inquiry will reap some benefits, but that doesn’t mean it’s an easy journey.”

Life after diagnosis and treatment

While the journey to receiving a formal ADHD diagnosis is often fraught with obstacles, many people who are diagnosed in adulthood highlight the increased perspective and higher quality of life gained after diagnosis and treatment.

English says although a diagnosis brought up some mixed emotions over lost opportunities, it also highlighted a self-appreciation for learning how to navigate certain struggles.

“Although it would have been nice to know [I had ADHD as a child], and I might have had a different life, it was probably for the best,” English says.

“I’ve learned these coping mechanisms of how to use my brain, to its best advantage, rather than being put into a corner and being [told] that, ‘You’re the problem.’

“Now I use medication to help me do things like keep my house clean and stay focussed at work instead of being a kid trying to work it out.”

May feels receiving a diagnosis and going down the medication pathway for treatment has “changed [her] world”.

“I think I never knew or understood what a calm, quiet mind felt like,” she says.

“I [now] feel like I have the ability to direct my focus, so I can choose what’s important; that was just not the case before.

“I would 100 per cent encourage anyone [who’s considering a diagnosis] to do it, because it can really change your life experience.”

As for Crees, receiving a diagnosis was “very emotional”, as it provided a sense of self-acceptance and understanding.

“I’ve heard it explained really well when people say, ‘What’s the point of having a label? It doesn’t make your life any better, so why bother?’,” she says.

“Being told I have ADHD doesn’t change my life; except I spent my whole life thinking I was a fail horse.

“Now I realise I’m actually a really successful zebra, and that’s great.

“I think it’s really important to recognise that [ADHD] is a neurodivergence and not a disability.

“[A diagnosis says], ‘You’re not odd, you’re not weird, you’re not unusual, you’re actually really special.’

“‘There’s also a lot of other special people out there; you just need to know that.’”

*Note: full names of some story subjects have been changed for privacy reasons.