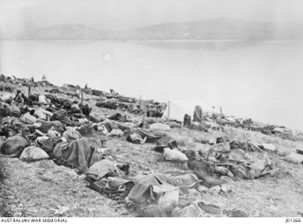

In the quiet corners of history, amidst the commemorated valour of Anzac soldiers, lies a trove of unsung heroism — the poignant chronicles of Gallipoli nurses like Anne Donnell. Their sacrifices during World War I are a testament to the bravery and resilience that is often overshadowed by the tumult of battle. (Image: The first batch of Sisters of No. 3 to arrive in Lemnos August 1915. Supplied: Graeme Mitchell)

By Prisha Mercy | @prisha_mercy

Graeme Mitchell, a 67-year-old Queensland resident, couldn’t have imagined how much a phone call from his brother would change his life.

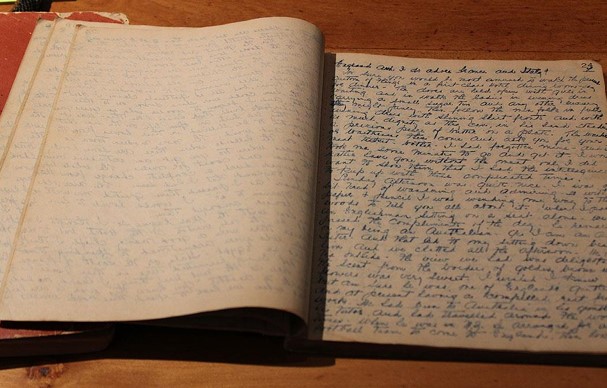

In 2006 Graeme’s brother, Rhett, called to say he had stumbled upon old diaries tucked away in a beauty case. Being the avid reader in the family, Graeme took the initiative to delve into them.

Looking at the diaries, Graeme had an intense feeling in his chest.

“I immediately knew that I was looking at a really big part of women’s history that hadn’t been explored,” Graeme said.

The diaries belonged to Anne Donnell Graeme’s adopted grandmother, who was one of approximately 2,300 nurses to serve as Anzacs during World War I.

“We had never been aware of Anne’s diaries and it’s a marvel they did not end up as landfill.”

Anne’s diaries sparked Graeme’s mission to transcribe the army nurse’s firsthand experiences alongside his partner, Jan Leader.

After eight months of meticulous work fuelled by cups of coffee and endless tears, Graeme and Jan finished transcribing the first draft of Anne’s diaries.

“History has a real way of overlooking people — we discovered that we needed to be really careful and aware that we were handling history from over 100 years ago that somebody wrote,” Graeme said.

“[Anne] was tired, hungry and scared, a long way from home, yet still managed to write so beautifully.”

“It was illuminating and we’re both better people for it.”

The middle child of five, Anne Donnell was born in Cherry Gardens, South Australia on October 31, 1875.

She began her service as an Anzac in Gallipoli during World War I, at the age of 39.

“You’d think how easy we’ve got it and how hard they had it,” Graeme said.

“Anne was only [small], but my goodness, she had the heart of a tiger and a warrior.

“She had a deep abiding care for the Australians — when you’ve got somebody who can’t fight … and they go into battle to care for people because of battle: that’s fucking bravery man.”

When the Anzac soldiers arrived at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915, Anne joined the ranks of nurses undertaking a relentless mission of mercy amid the chaos of war.

She served in the 3rd Australian General Hospital (AGH) on nearby Greek island Lemnos, under the leadership of matron Grace Wilson.

In the dimly lit hospital and transport ships, anchored precariously offshore, the nurses tended to the wounded with unwavering devotion.

Despite being away from the battlefield, the nurses were not immune to the dangers of shelling. Stationed on a hospital ship, many Australian nurses found themselves close to the frontline during the Gallipoli campaign, where they encountered perilous situations.

Take September 5, 1917, when Anne and her colleague Sister Mary sought shelter in their dug-outs at the first sign of danger:

I’m certain I hear the drone of the enemy again … I’m sure he is … directly above us … bang went the first gun, and immediately followed the most terrific crashes and explosions … I thought our numbers were up … a few seconds more and we would be facing eternity … It was awful. Short sharp and loud, then quietness. The guns had stopped firing. And we hear our own Aeroplanes going up … but we kept in our dug-outs.

The nurses experienced fear, anxiety and a profound sense of homesickness just as the military personnel did.

Anne wrote:

We still watch the Southern Cross at nights but only 3 more nights to see it. Then I wonder when we shall see it again… Why is Australia so very far away?

Amidst the unforgiving chaos of October 21st, 1915, Anne penned words that echoed both resilience and devotion:

We are really roughing it but most of us are as happy as can be … as long as we can benefit the boys in making them better, comfortable, and contented we do not mind.

According to Peter Rees, an author specialising in Australian military history, Lemnos presented “the worst conditions nurses could face anywhere in the Great War”.

Grace Margaret Wilson (1879 – 1957) was the principal matron at the 3rd AGH between 1915 and 1919, treating casualties from the Gallipoli campaign.

Matron Wilson, who arrived in Lemnos shortly after her brother’s death at Gallipoli, was appalled by the inadequate equipment and dire conditions.

Leading by example, she organised the chaos at the tent hospital and persisted alongside the nurses, treating more than 900 patients within a month.

Sister Frances Selwyn-Smith wrote of Wilson’s leadership:

At times we could not have carried on without her. She was not only a capable matron, but what is more, a woman of understanding.

However, matron Wilson also had to contend with old-fashioned officers who viewed nurses as inferior to male orderlies, despite their similar social standing.

Sister Edna Pengelly, who served from 1915 to 1919, reflected on the military’s stance in her diary entry dated November 6, 1916:

Sisters have no status at all, clinical machines are what we are supposed to be – or ought to be – I suppose – to please them.

The presence of women within earshot of gunfire offended some officers. Sister Olive Haynes from 2nd AGH recalled her time in Heliopolis in 1915 as unpleasant, stating: “This is a beastly place and we are not wanted.”

Despite their dedication, the nurses’ sacrifices and contributions were overlooked, leaving them feeling undervalued and disheartened.

History Professor Melanie Oppenheimer from Australian National University said: “We know the Gallipoli campaign was a complete failure.”

“Ignoring the role of nurses stems right to the fundamental point that women were not in the Peninsula physically, and therefore excluding them from Anzac mythology.

“If the women had been there, the Anzac mythology might have had a different flavour to it.”

However, Professor Oppenheimer noted that Australian soldiers viewed nurses as equal.

“The nurses were called ‘Anzac Heads’, indicating their integral role in Australia’s fighting force,” Professor Oppenheimer said.

“The soldiers themselves very much included the nurses as being a part of the Anzac story, but it’s [because of] the people at home, and then subsequent years, that [nurses] just don’t get the prominence that the men do.”

Lieutenant Harold Williams was one of the soldiers who observed that despite the AGH “reeking with odours of blood and unwashed bodies,” the resilience and dedication of these women spoke volumes about their strength and commitment.

In Lemnos, Australian nurses also faced financial hardships. Positioned at the bottom of the pay scale, they struggled to afford necessities, having to purchase extra food from canteens and vendors.

Additionally, nurses like Anne suffered from grief and loss.

In Anne’s diary dated July 5, 1917, she wrote:

The days were gone before you knew it, and you felt you hadn’t accomplished anything, but this laddie in the corner I thought he shall have some special care, and I told him he would be mine until his mother came. He gave me the loveliest smile … next morning his bed was empty, just another one of many.

The constant work and high fatality rate took a toll on their physical and mental wellbeing, as expressed in the diaries of Sister Kath King and Sister Ella Tucker:

I have such a nice boy, too sick to be moved … My patient died at 10.10pm. My nineteenth death in a fortnight, and such lovely boys. Am just heartily sick of the whole of the war. (Sister Kath King)

The wounded from the landing commenced to come on board at 9 am … two orderlies cut off the patient’s clothes and I started immediately with dressings. There were 76 patients in my ward and I did not finish until 2 am. (Sister Ella Tucker)

Among the Anzac nurses, there was an unspoken understanding that each had a connection to someone — whether a family member, a friend from home, or a familiar face from their past — whose fate remained uncertain.

In the hospital wards, whispers of concern about the soldiers’ welfare filled the air. Together, the nurses bore the weight of this collective anguish, tirelessly attending to horrific injuries that training could not have prepared them for.

Professor Oppenheimer noted that prior to the war, nurses had no experience in military nursing and treating gunshot wounds.

“They were basically learning on the job because they hadn’t experienced this sort of nursing before…They were literally thrown on the deep end,” she said.

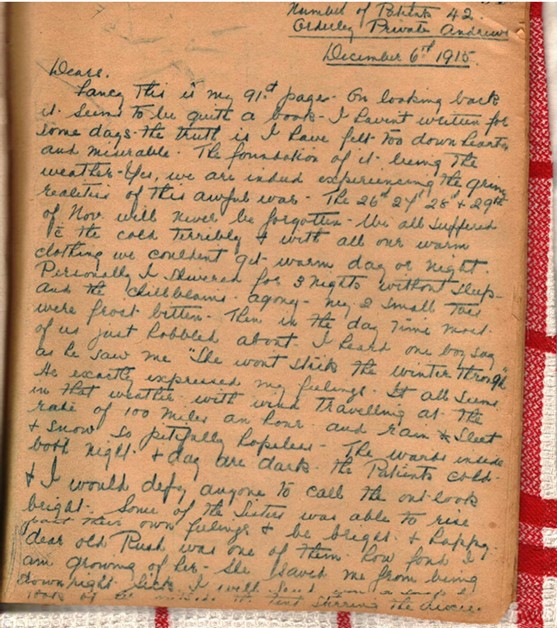

Harsh weather conditions were another challenge for nurses during the war. Nurses working in Lemnos were often housed in flimsy tents in freezing conditions and gale-force winds. They grappled with scarcity of food and dysentery, all the while tirelessly attending to the multitude of wounded souls in their care.

In late October, Anne described the dismal autumn atmosphere:

The weather is terrible, bitterly cold, with a high wind and rain. We are nearly frozen, even in our balaclavas, mufflers, mittens, cardigans, raincoats and Wellingtons. It’s a mercy we have ample warm clothing else we should perish. Last night five tents blew down …

I haven’t written for some days … We all suffered with the cold terribly … I shivered for 3 nights without sleep … my 2 small toes were frost bitten … I heard one boy say as he saw me: “She won’t stick the winter through.” He exactly expressed my feelings.

Their days blurred into nights; each moment was fraught with uncertainty. However, amidst the grim realities of war, the nurses became beacons of hope. Their gentle touch was a balm to the wounded.

Finally, Anne Donnell wrote in her diary:

Goodbye Lemnos. We take away many happy memories of you. I would not have liked to miss you, yet I have no desire to see you again.

Her words echoed the heartache of bidding farewell to a place where joy and sorrow intertwined and where camaraderie and resilience coexisted with the haunting echoes of trauma, loss and suffering.

In the aftermath of Anzac, Anne pursued her noble quest in social care and aided humanity’s most vulnerable with unwavering empathy. From children’s laughter to veterans’ tears, she offered solace and support, leaving a legacy of enduring compassion in a world too often besieged by hardship.

Anne passed away the year before Graeme Mitchell was born.

“Some friends took her in, and she died in a granny flat underneath the house,” Graeme said.

“It was appalling how we cared for those who came back.”

“Anne Donnell earned the right to stand shoulder to shoulder with the best this country’s ever had and we should be fucking ashamed that we let one of the bravest pass on like that.

“This woman was an absolute warrior — wherever she is, whoever’s travelling with her now is in the presence of greatness and I am incredibly pleased that I was chosen by the universe to tell her story.”

Professor Oppenheimer emphasises the need to broaden Anzac Day’s focus beyond masculine endeavours and, instead, highlight the importance of recognising nurses’ roles for a more inclusive remembrance.

“Society is not just men; women were there too,” Oppenheimer said.

“It just doesn’t tell the whole story — by focusing on masculine endeavours, it’s one-dimensional.

Nurses made sacrifices like men — they come home traumatised too [and] we need to include them.”

In Frontline Hero, Graeme and Jan wrote: “Australia has many warriors. Some are recognised; far too many lie here and in faraway lands, gently embraced by Mother Earth and laid to immortal rest…

“They are all worthy of our respect. Anne and many fellow First World War nurses never received the care and recognition post-war that they themselves had given so selflessly to our soldiers during the war.”

“One thing I’d really like is to see a memorial for Anne in Cherry Gardens where she was born,” Graeme said.

“I want people to understand the horror of war and [why] we don’t need it.”

“I’d love to see her name remembered in schools.”

In the tapestry of time, Anne Donnell and her fellow nurses transcend mere heroism; they embody humanity’s rawest emotions.

Let us not make their stories a mere footnote in history, but rather, an everlasting tribute to their unparallelled bravery and sacrifice.

Lest we forget.