Votes for minor parties and independents surged at and since the 2022 federal election. Why is this? OTR’s Political Editor Robert Hicks takes a look. (Image: Australians voting at a polling booth. Sourced from AEC Images, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

By Robert Hicks | @_roberthicks

Kristy Wells, 45, sits at the table in the dining room of her lively and often cramped northern suburbs house.

She pulls at a worn pink plastic bone in her dog’s mouth as she says: “I don’t care who’s doing it as long as the little guys win.”

The big guys — politicians — don’t do enough, she thinks.

“They’re all a bunch of whingers in parliament house.”

When it came time to vote in the 2022 federal election, she described her choice in the upper house — the Senate — as “really random”, but she gravitated towards minor parties like Legalise Cannabis and those focused on the environment and health rights.

“I vote for the little guys.”

But for the lower house — the House of Representatives — there weren’t as many options as in the Senate.

She lives in the seat of Spence, in Adelaide’s outer northern suburbs, where six parties ran candidates: the Liberals, Labor, the Greens, One Nation, United Australia, and the Federation Party.

She voted for One Nation.

“I like Pauline Hanson, actually. She’s a tough bitch,” she says.

“The economy’s all gone to fuck. Interest rates are through the roof, inflation’s through the roof, unemployment’s through the roof.

“Pauline Hanson looks out for the little guy.”

Wells’s choice is not an anomaly, but part of a growing trend.

She was among the 700,000 Australians who cast their ballot in favour of One Nation — and the 4.5 million who didn’t put a major party as their first preference.

But why is this occurring?

Wells says the major parties are “just as bad as each other”.

One Nation Senator Malcolm Roberts agreed, saying his party’s inherent appeal is “that we listen”.

“Both wings of the uniparty, Liberal and Labor, are not capable of listening … they go out and listen but are not capable of doing anything about it because party policy is outside of them,” he says.

“Pauline has no fancy political philosophy, she just has one — if it’s in the national interest, we do it.

“They’re also seeing that [pattern of]: Albanese, Dutton; Labor, Liberal; Tweedledumb, Tweedledumber.”

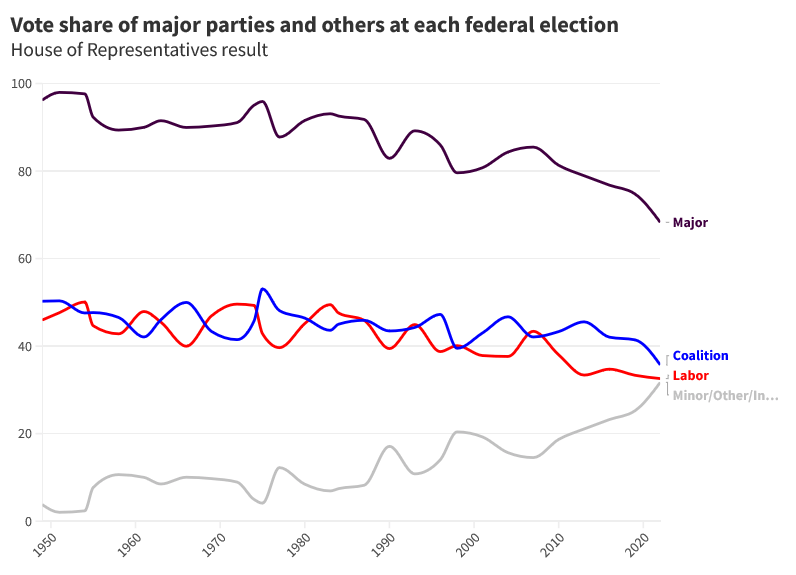

According to Griffith University Associate Professor Paul Williams, the increase in alternative votes has been brewing slowly.

“The key point is they’re not suddenly doing it — this is a very long process.”

While the representation of minor parties and independents in parliament is at an all-time high, it reflects a gradual increase in votes towards alternatives as the Liberals, the Nationals, and Labor slowly shed votes.

“This has been occurring for decades,” Williams says.

The last time the major parties combined received over 90 per cent of votes was at the 1987 federal election.

The 1998 election saw major party votes drop below 80 per cent. Votes rose to the low-to-mid 80s until the 2013 election — where they dropped to 78.93 per cent and kept falling.

The 2022 federal election was a new low for the major parties, who received 68.28 per cent of votes combined.

While this may be normal in multi-party democracies, Australia only had such instances between 1901 and 1909 when there were three major parties, and never in the period of two-party hegemony.

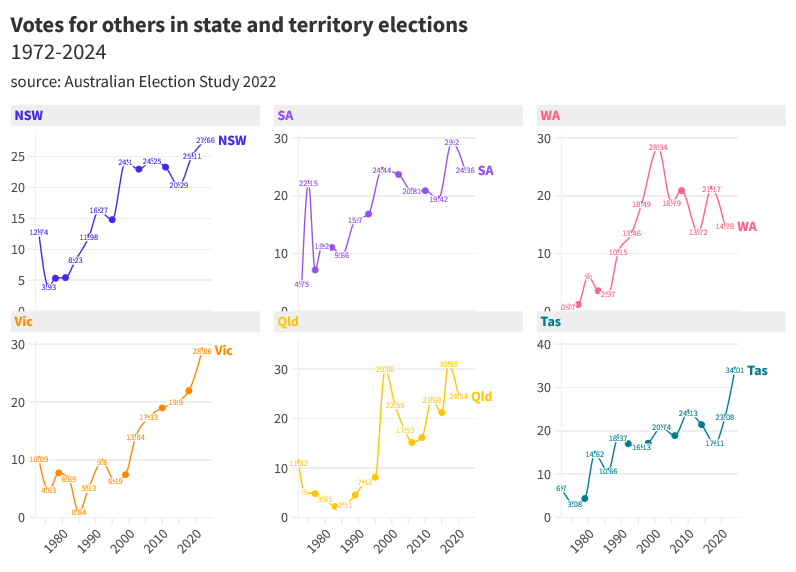

It’s a similar story at a state level.

At each state’s last election (except for Western Australia) major parties won between 65.67 per cent and 75.64 per cent.

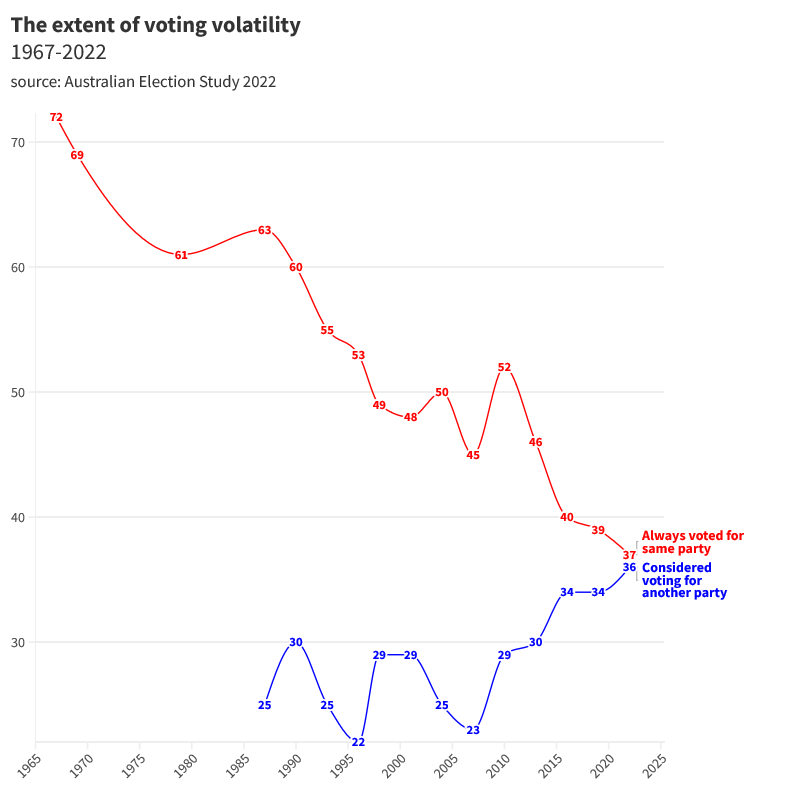

Part of this can be attributed to increasing levels of voting volatility; according to the Australian Election Study 2022, people are now more likely to switch their vote at an election than they have ever been before.

Regardless of voting systems, votes for minor parties and independents are rising — but the ability to win helped the trend according to Williams.

“We have proportional representation in the Senate, which gives life to minor parties,” he says.

“In Australia we have preferential voting in the lower house federally and [in] most states — except Tasmania — which makes minor parties useful and relevant.

“And then of course in upper houses and the lower house in Tasmania, we have proportional representation, which means minor parties can get elected on a fraction of the vote, which makes them more than relevant and makes them a serious player.”

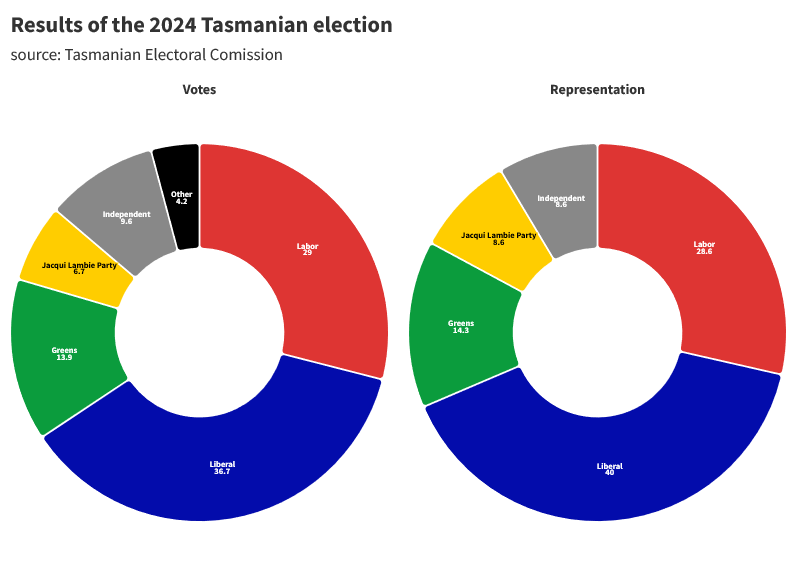

At the Tasmanian election this year, minor parties and independents won 34.33 per cent of the vote and won 31.42 per cent of the seats in the Tasmanian House of Assembly.

It forced the incumbent Liberal government to negotiate with the Jacqui Lambie Network and several independents to maintain power in a minority government — an arrangement where the party that forms government doesn’t control a majority of seats and must turn to other political players.

But according to Strategy and Campaigns Director of RedBridge Group Kos Samaras, the major parties misread the electorate during the campaign.

“The worst thing those major parties did during that state election was to go and say: ‘If you vote for a minor party or independent there will be a minority government, there will be chaos,’” he says.

“But they didn’t understand that a ton of Tasmanians thought that was a great idea.”

It’s not just Tasmanians, either. A majority of the Australian public don’t think that minority government is inherently bad for governance.

“We’ve got a poll coming out in the next two weeks where we asked the question: ‘Do you agree with the following statement: minority federal government equals economic chaos,’” Samaras says.

“Only 35 per cent agree with it.”

Williams says there are a few reasons for this.

“The most cited [reason] is what we call ideological convergence … a belief that the major parties are too alike,” he says.

“Tweedledumb and Tweedledee, they’re often called: ‘They’re the same bottles with the same labels and each equally empty,’ was what we used to say about the Democrats and the Republicans in the United States as well.

“That reason is less important today because there has been ideological divergence in more recent times. Since the rise of One Nation, you’ve seen the Coalition move to the right and leave the Labor Party.”

Historically, divergence coincided with the rise of the Australia Party in the early 70s and the Australian Democrats in the late 70s until their decline in the late 90s. Both occupied the political centre.

“People saw the two major parties as sinful, as vacuous, as too alike, and they’re looking for a third alternative,” Williams says.

“And then again in, and certainly after, 1990 for the rise of the Greens, [as] a lot of left leaning people feel the Labor Party is too right-wing and want to vote for the Greens. And similarly, they see the Coalition as too left-wing, and they want to vote for One Nation [or others].

“I’d say in the last 20 plus years ideological conversion is not a strong reason, but the last 20 years also coincides with the expansion of the internet … with the rise of social media.

“These things are contributing to volatile electoral behaviour because they’re giving cheap and free avenues for minority and fringe voices.”

Demographic switch

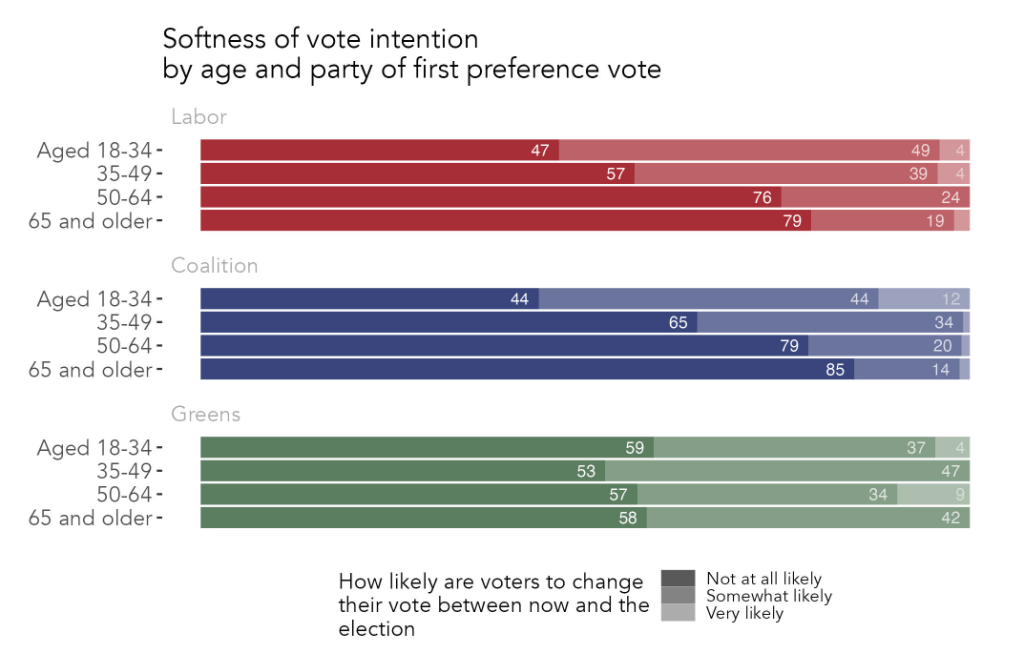

A recent public opinion polling report conducted by RedBridge Group highlights the softness of votes — how likely someone is to switch their vote to another party.

In general, younger major party voters are more likely to switch their vote than their older counterparts.

However, young Greens voters are the highest proportion of Greens voters to report they won’t change their vote.

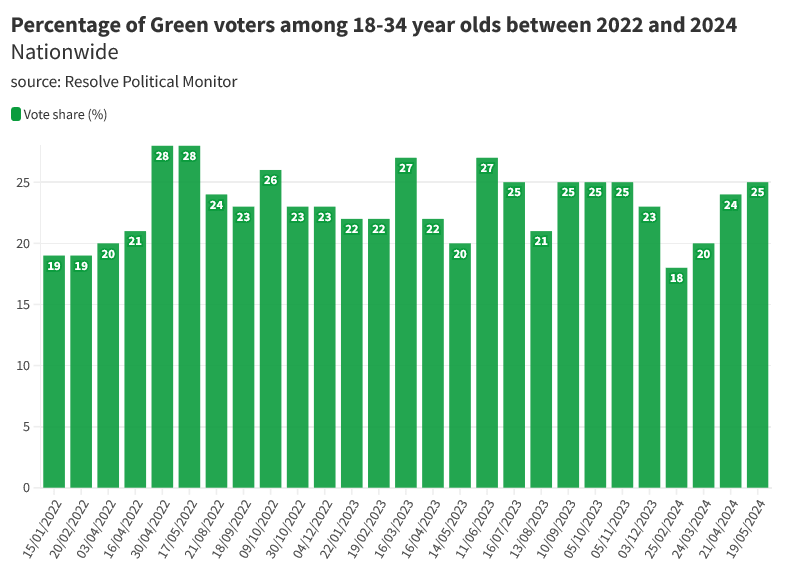

Samaras says: “[According to the RedBridge Group poll] the Greens are doing really well amongst younger voters, really well — 18-to-34-year-olds are up to about 20 per cent.”

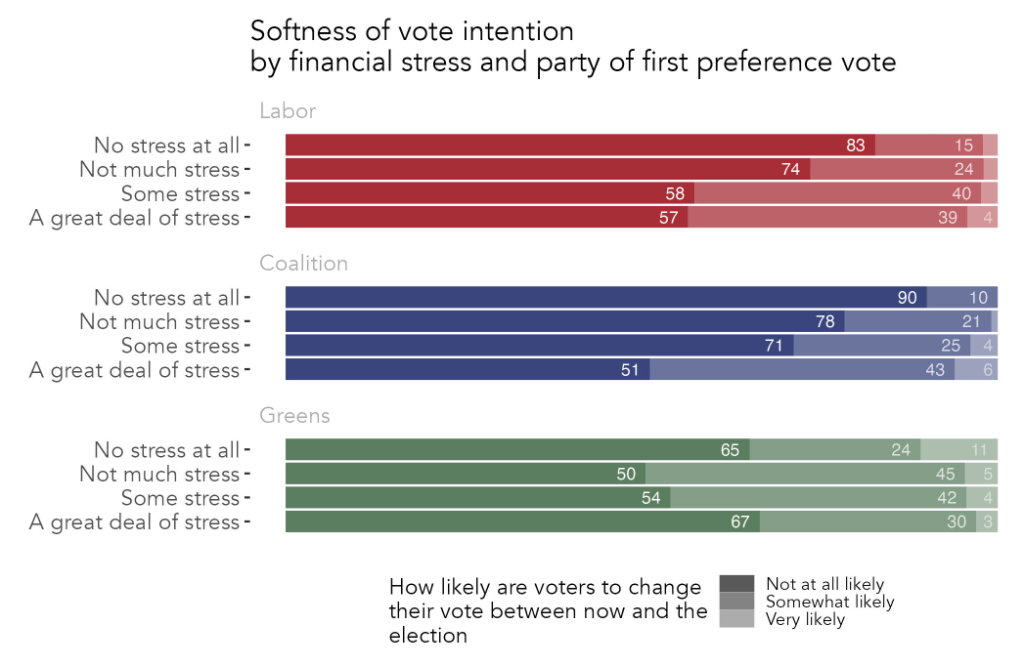

“That, in contrast, [is] 3 per cent with boomers and over for the Greens.” Reported financial stress also correlates with a softness in votes — except for Greens voters.

“The Greens are the party that you go to if you’re progressively minded and if you’re struggling in terms of income because they are challenging the system,” Samaras says.

“Overwhelmingly, people who are sitting on minor parties and experiencing financial stress have a very strong view that the system is stacked against them.

“They blame the major parties for it and the whole establishment.

“And, so, you’re more likely to be quite firm in your views with regards to support for the Greens if you’re in that space.”

Williams says support for Labor, the Greens, and other left-wing parties is highly concentrated amongst certain groups.

“The two fastest growing influential demographics in Australia are women voters and young voters,” he says.

“And so, young [people] and women, and especially young women — young, tertiary, educated, white collar women — are really game changers. They’re almost like the gatekeepers for who’s going to get elected.”

Zali De Pizzol is a 23-year-old teaching student who comes from a Liberal voting family, but she’s never had the same views.

“For as long as I can think of, I feel like I have had more progressive views,” she says.

When it came time to vote in the 2022 federal election, she says she “didn’t really think critically about it”, but that feeling spurred some research.

“For me, it was [that] I didn’t really like anything that the Liberal Party [was] doing.”

De Pizzol says she “didn’t like the kind of politicians that they had” and did not agree with the opinions of people she knew who voted Liberal.

“Well, obviously, I don’t think I align with them.”

“And then I always had [the] opinion, as a lot of people do in Australia, of: ‘OK, if you don’t vote Liberal, you vote Labor,’ and then I had looked into Labor as well.

“The Labor Party says that they’re left but they’re very centrist. And I don’t like that they claim to be more progressive when it comes to climate and then they’re still getting donations from fossil fuel companies.

“So, for me I was like: ‘OK, well, I have heard of the Greens and I had always thought from when I was younger that maybe the Greens weren’t really an option.’

“And then I looked them up.

“I was reading their policies, I saw some of their politicians, and I was like: ‘I think that’s how I’m gonna vote.’”

In South Australia, where De Pizzol is from, and in other states aside from NSW, Victoria, and Queensland, the April 21 Resolve Political Monitor had the Greens polling at 17 per cent. Among the 18–34 age group between early 2022 and late 2024, it hovered between 18 and 27 per cent.

SA Greens co-convener and candidate for the SA Greens at the 2024 Dunstan by-election Katie McCusker says: “It’s just absolutely skyrocketed.”

“I think that is off the back of the Dunstan campaign that we have here,” she says. “But the Greens are more visible than ever; we’ve got more representatives in parliaments which means more media engagement, more comments — people are getting to know us.

“But what’s really making the difference with the votes, whilst all those things are great and are adding to it, is that we’re having the one-on-one conversations,” she says.

“What we’re finding is that people already agree with our policies. They want what we’re offering.

“But what the barrier is for them is they don’t believe the Greens can actually win.”

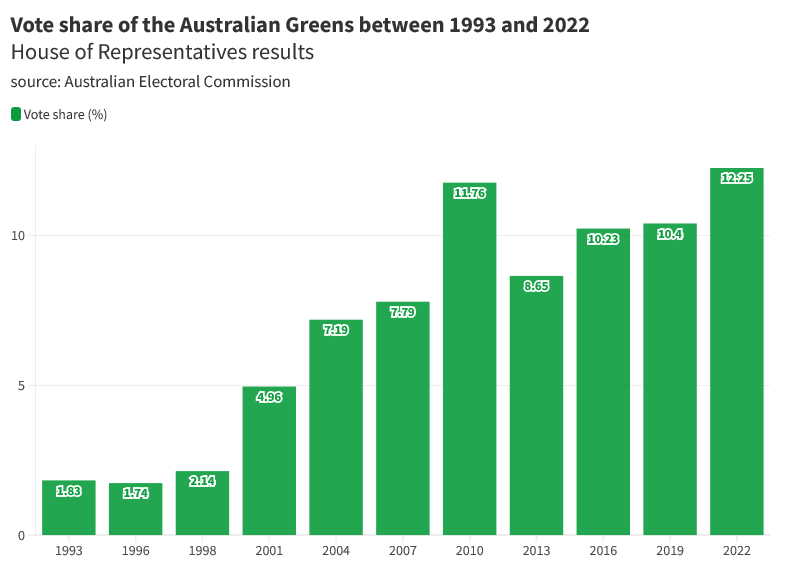

At the last federal election, the Greens won a record vote of 12.25 per cent.

They won the inner-city Brisbane seats of Griffith, Ryan, and Brisbane — all highly educated, young electorates.

Samaras says these results reflect a trend across Western democracies.

“University qualifications have a stronger correlation with voting behaviour now than [they] ever did before. You’re more likely to vote for a party of the left if you’ve got a university degree.”

Samaras says anyone under the age of 40 is also more likely to be a tactical voter but support left-wing parties overall.

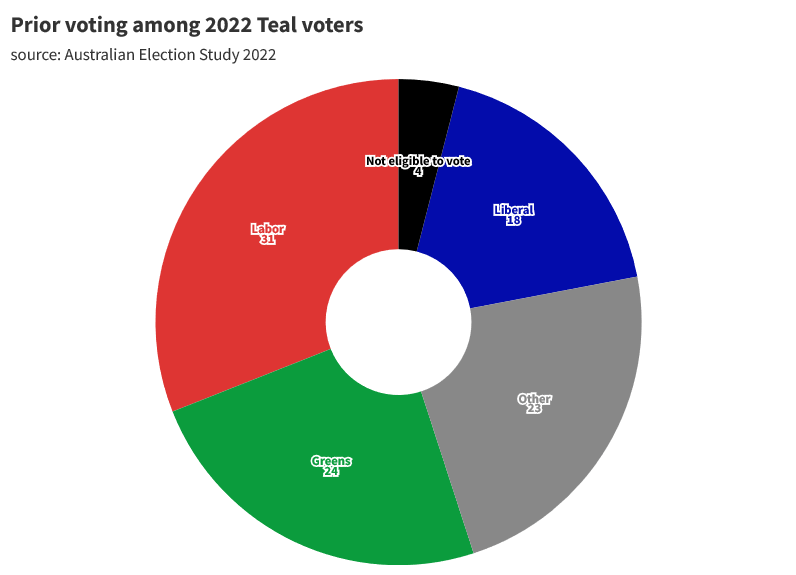

“They will, for example, choose to vote for a Teal independent because it removes the conservative,” he says.

According to the 2022 Australia Election Study report, voter disenchantment with major parties has not materialised in alternatives being elected until now — the requirement was a viable alternative: a role which the Teal independents filled.

The success of the Teals — socially progressive, economically-liberal independents in inner-city Melbourne, Sydney, and Perth — was the story of election night, buoyed by anti-Morrison feelings and concerns regarding climate action, political transparency and a Liberal party lurching to the right.

Climate 200 Convener Simon Holmes à Court likened the role of Teal independents to something he first heard from American polymath Buckminster Fuller, who Holmes à Court says “likened himself to a trim tab”.

What is a trim tab? To explain to the crowd at the ‘Adelaide is doing politics differently’ event in April, Holmes à Court recalled the Queen Mary, once the world’s largest ocean liner, and focused on its rudder.

“When it’s going full steam ahead in the water that rudder is rushing past hundreds of tonnes of water every second,” he says.

“And if you want to try to move it, it’s almost impossible to move against that wall on both sides.

“Right at the end [of the rudder] is that little thing … called the trim tab.

“It makes it really easy to turn the rudder and once you turn the rudder, gradually, over minutes — not immediately, but over time — the boat turns around.

“And, so, with the application of the right amount of pressure, at the right point, at the right time, you can move the right people and then those people can turn the ship — the state — around.”

But Teal voters are different. The ideal Teal being a ‘disaffected Liberal voter’ holds some truth but obscures the large proportion of former Labor, Green, and other minor party voters strategically voting to oust the Liberal incumbent.

The common thread

Senator Roberts recalls an experienced One Nation scrutineer who was baffled by people putting Greens first, One Nation second, and vice versa.

“But what we’ve worked out is that some people are voting Greens because they don’t like the uniparty and some people are voting One Nation because they don’t like the uniparty,” Roberts says.

De Pizzol believes that the Liberals and Labor “like to think that they’re not [that similar]”.

“But I think there’s so many things that are alike between the two of them, and between them it’s just picking apart the policies that are, at the end of the day, much the same,” she says.

Samaras is constantly polling the electorate. Just this week, RedBridge was interviewing One Nation voters and asking: “What do you think of the growth of the Greens in other parts of the country?”

“Their response was: ‘That’s great. Good on them. Stick it up them,’” Samaras says.

“They view every other player in the mix that is tearing down the majors as a positive even though they’re probably conservative.”

McCusker knows that most people are disengaged, and most are “just trying to get by each day, and so they haven’t got time to think about politics”.

“They’re not sitting down with a broadsheet every morning over a coffee. These are people who just hear something and go: ‘Yep, you’ve got my vote because I connect with that, and I want something done about this,’” she says.

Many, including Wells, want change.

“I could tell you very little about politics,” she says.

The most she’s exposed to politics is through the TV in her workplace’s break room — Question Time on ABC News often plays as she walks in.

Her first thought is always: “Oh, this shit?”

She’ll always find the remote and change the channel.