Harry Hutchison-Smith is one of many young South Australians unable to leave the nest thanks to the rental crisis. (Image: Chelsea McLean & Canva 2024)

By Chelsea McLean

South Australia’s rental crisis is pushing young adults into desperate living situations. This includes moving back home, multi-generational housing and homelessness. Youth Allowance is not being adjusted to this crisis, which is disadvantaging young adults.

Recent data from PropTrack’s Rental Affordability Index shows that South Australia is at its lowest affordability rate in at least 17 years, with an average rental price of $540 per week.

According to Believe Housing Australia, more than 50 per cent of renters in the state are in severe housing stress. Housing stress occurs when lower-income households spend more than 30 per cent of gross income on housing costs.

Ella Crossland was 18 when she moved out of home and rented with UniLodge at the Magill student housing complex in 2022. UniLodge is a purpose-based student accommodation offering cheaper rentals.

“I originally moved out of my family home to live closer to my university, since my family lives in Victor Harbor,” Crossland says.

Crossland’s income came from her weekend job and Youth Allowance. Youth Allowance is a Centrelink payment that financially assists young students. Crossland also received rent assistance on top of her Youth Allowance payments.

According to the South Australian Council of Social Service (SACOSS), people on Youth Allowance experience the deepest poverty. Housing status is also a major poverty risk, with one in five people renting privately living below the poverty line.

“Money was a huge problem. I could barely afford food. I would rely on free breakfasts from my university and food from my family,” Crossland says.

“I didn’t receive much from Centrelink, and this really made renting stressful. In fact, money was a big reason why I moved back in with my parents.

“I just couldn’t take it anymore. Balancing full-time study with work and living at UniLodge was just too much.”

Premier of South Australia Peter Malinauskas says he is aware of the impact of this crisis on young adults.

“Our rental market is the tightest it has been for a generation, and that has a real-world impact on families, especially young people who are trying to establish careers, grow families and make their way in the world,” Malinauskas says.

“I’m particularly concerned about what the pressures in the housing market mean for those young South Australians looking to make the decision to leave the nest.”

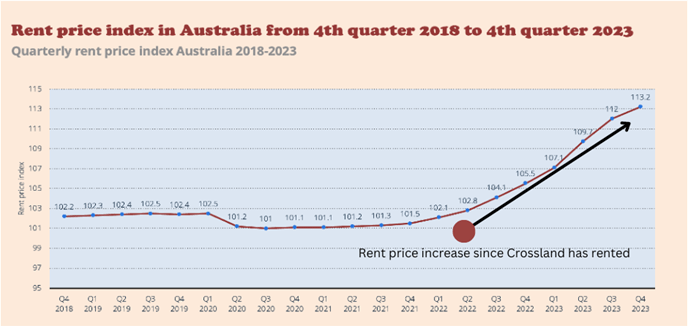

Since Crossland’s stay at UniLodge, there has been a 10.2 per cent increase in rental costs according to SACOSS.

SACOSS data on the increase in rent prices from 2018-2023. (Image: Chelsea McLean & Canva 2024)

“I am not considering renting anytime soon,” she says.

“If I struggled so much with renting back then, I can’t imagine how bad it would be renting now with higher rent prices.”

Crossland is not the only young adult forced to move back home due to rental unaffordability. For 21-year-old Harry Hutchison-Smith, high rent prices meant that he couldn’t save his earnings. This caused him to move back in with his parents.

“The thing that drove me out of home initially was mainly because I wanted my own space. I’d just started studying and working full-time in the city, so it seemed like a good idea at the time,” he says.

“My income was pretty good … However, much of my income did go to rent and living expenses. It’s difficult to save when renting.”

Hutchison-Smith says the main thing that drove him to move back in with his parents was that he couldn’t save money.

“The other part was that rent was going up and I couldn’t really justify living there anymore, as my study was also finishing up,” he says.

Hutchison-Smith says he has no intention of renting again: “I would probably try and buy my own place before renting again, which has been my main saving goal.”

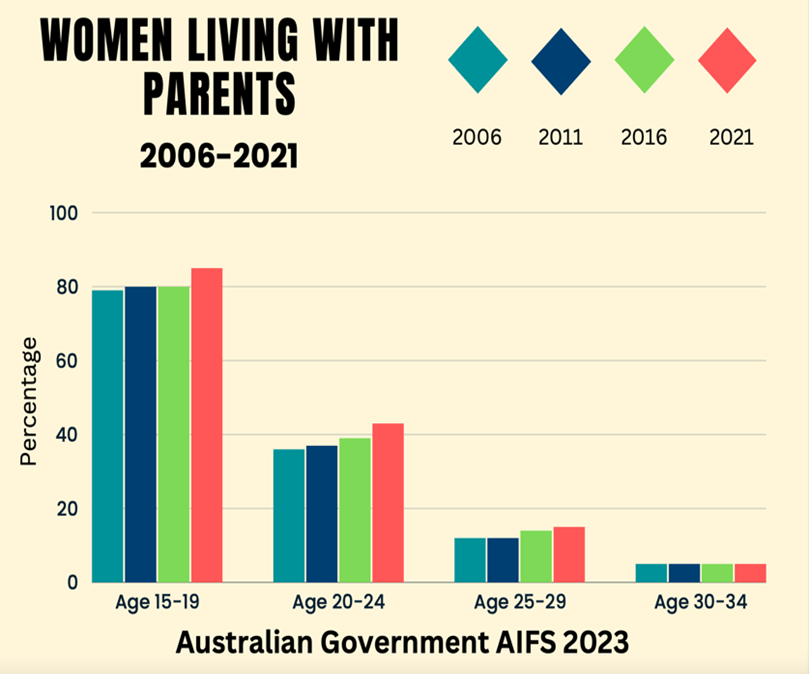

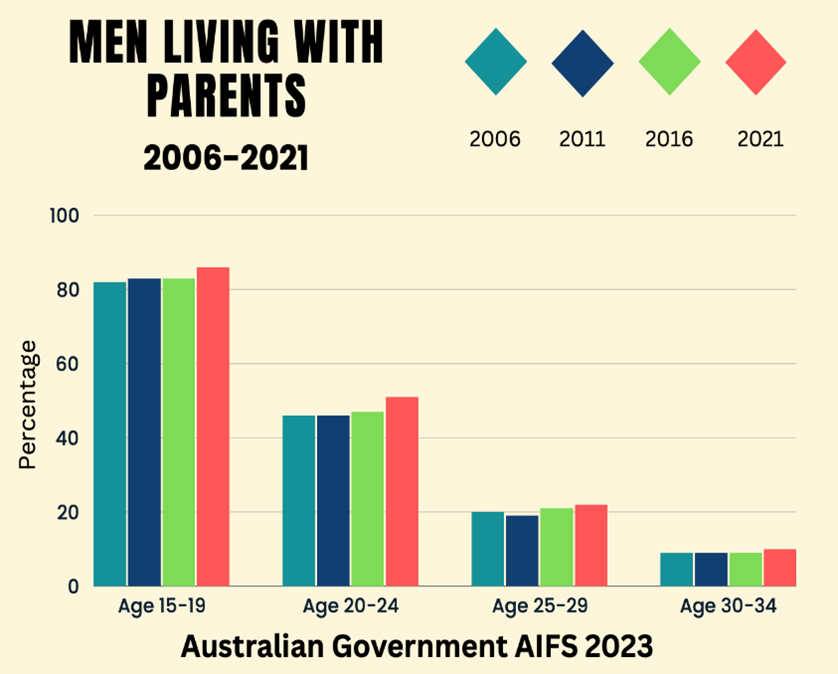

As rent prices and cost-of-living concerns accelerate, young people are increasingly living with their parents for longer periods of time. This reflects the rising difficulty in gaining and maintaining independence.

Recent data from the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) shows an increase in men and women living with parents. (Image: Chelsea McLean & Canva 2024)

Young adults are unable to live independently on Youth Allowance.

The state’s overwhelming rent price increase has left no homes affordable for a person living on Youth Allowance, according to a 2024 rental affordability snapshot by Believe Housing Australia. This is leaving young renters, like Crossland and Hutchison-Smith, with no option but to resort to dependent living.

The biggest concern for Hutchison-Smith and Crossland is the lack of Youth Allowance support due to its distribution of money based on parents’ income. The current system provides less money to students whose parents’ income surpasses the limit of $62,634 annually. Students can only earn support without the influence of parental income once they reach Centrelink’s independent age of 22.

The current system leaves relocating young adults under the independent age with inadequate support.

Crossland says: “I don’t think it’s fair to judge how much income you earn with the money that your parents earn because in the end, it’s your money — not your parents’.

“Sure, your parent can help you, but in the end, it depends on the willingness of the parent to help, not their income.

“I would probably still be renting now if I had good Centrelink support.”

Hutchison-Smith says: “I did not receive any Centrelink benefits when I rented as my family made too much money despite being split up.”

Uniting SA, a non-for-profit youth assistance organisation, is aware of the financial burdens for young people relying on Youth Allowance while renting.

Uniting SA senior executive of community services, Daniel Cox, says: “When young people get some work or secure Youth Allowance, it is not enough.”

“It is not enough to give yourself a rental property on your own, nor to be able to manage study whether it’s school or post-school study.”

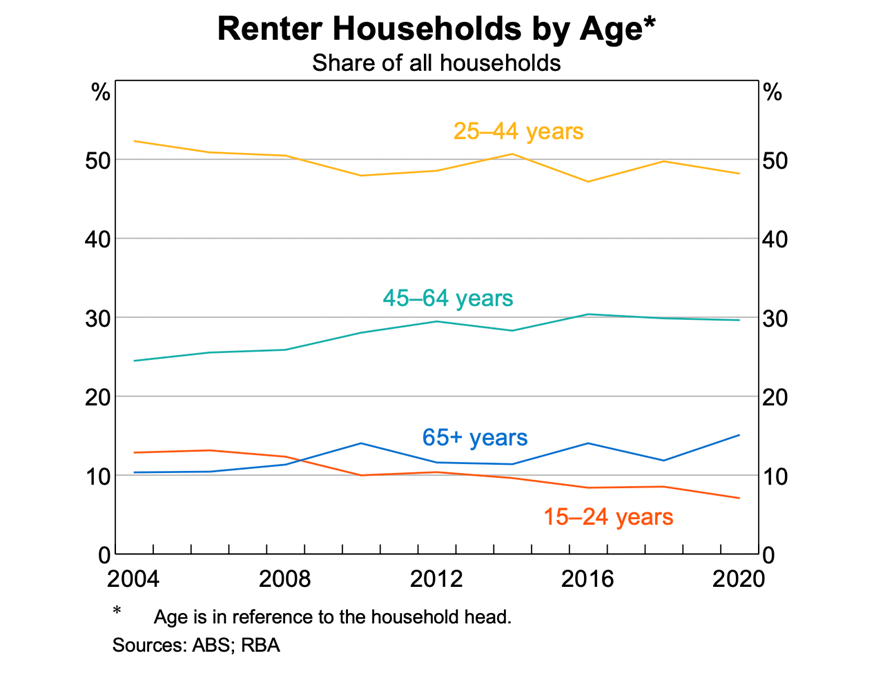

Cox is right — there has been a decrease in young renters over time as living becomes less affordable.

Renter households by age. (Data source: The Reserve Bank of Australia and Australian Bureau of Statistics 2023)

Senior property manager at Hunt & Hunt Property Kerry Todd explains that the decrease in young people renting is also a result of high interest rates, as investors cannot afford to maintain their properties.

“We are losing quite a few properties to the sales market because investors can no longer afford to maintain them. That is falling back on how many properties we can supply to tenants,” Todd says.

“This has a profound effect on the younger generation being able to be approved for a rental property because these properties would also more likely go to experienced renters and families.”

Youth Allowance is currently the lowest of all government payments. Greens member of the South Australian Legislative Council Robert Simms believes support payments should increase.

“My colleagues in Canberra are pushing to make life as a young independent person more manageable by increasing Youth Allowance,” Simms says.

“The Greens have advocated to increase all income support payments so they are above the poverty line.”

The rental crisis is pushing young families into multi-generational housing as South Australia’s population increases.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics reports there has been a national increase in three-generational living arrangements from 275,000 in 2016 to 335,000 in 2021. The rise in multi-generational housing is a result of population growth, increasing rental costs and low vacancy rates.

Much of Australia’s population growth is due to migration. Migration is beneficial for Australia’s economy as immigrants bring new ideas, produce international connections and fill labour shortages.

Post-Covid in 2022-2023, overseas migration increased from 427,000 arrivals to 737,000 according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This is a 73 per cent increase. More people migrate to Australia than migrate away, with a two per cent decrease in departures recorded in 2022-2023.

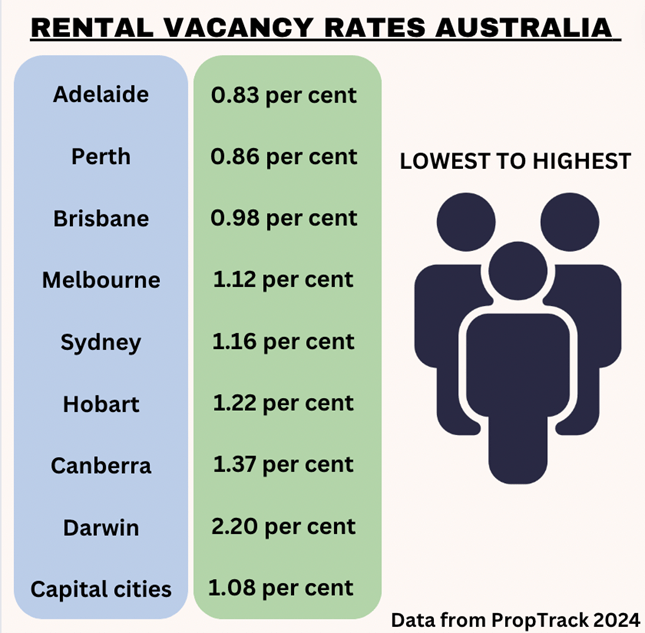

The surge in migration has added further pressure to an already-stretched market as more young immigrants are becoming renters. Monthly data from PropTrack shows that South Australia has the lowest rental vacancy rate in Australia at 0.83 per cent with the national vacancy rate in capital cities at 1.51 per cent.

“A healthy vacancy rate is normally around three per cent,” PropTrack senior economist Anne Flaherty told the ABC.

Rental vacancy rates Australia 2024. (Image: Chelsea McLean & Canva 2024)

Immigrants and South Australian citizens by birth are taking up multi-generational housing, whether due to cultural or economic influences.

In the case of economic influences, the push for multi-generational housing reflects the state’s alarmingly low vacancy rate as families are unable to find a home.

Simms says: “With an ever-lowering vacancy rate in South Australia and lack of affordability, moving in with family is becoming a favourable option for many individuals, and I absolutely believe that South Australia’s housing crisis has contributed to this increase.”

For 20-year-old Courtney Byrne, multi-generational living was the only option for her family to gain a roof over their heads.

“I had to move into my grandparents’ house with my mum and stepdad,” says Byrne.

“We had to move out of our old rental with not much notice. They just told us to pack our bags and leave. We had no savings because we had so much to pay for.

“My grandparents took us in, which definitely helped to relieve the stress. However, it did feel strange living with them as I don’t talk to my grandparents very much.”

Byrne’s mum and stepdad moved out of the three-generational living arrangement a year later.

“When we first looked for a rental, it was $300-$400 per week and now looking for a new place, it’s like $500-$600 for a two-bedroom rental.

“Because we have four pets, we had to find a rental that allows them, and landlords prefer people without pets.”

The South Australian Government reported: “Targeted consultation is … underway on a range of amendments to the Residential Tenancies Act including to prevent landlords unreasonably refusing a tenant’s request for a pet.”

Byrne’s family was able to find a rental prior to moving out of the multi-generational living arrangement but is now on the house hunt again.

“The landlord at our current rental wants to move back in, so she is giving us a few months to move out,” Byrne says.

“Nan doesn’t want us back because we put more financial responsibility on her, but she said she’ll let us move back in if we are in a crisis again.”

When multi-generational housing doesn’t work, intergenerational poverty and family breakdown can leave young people worse off.

Uniting SA’s Cox says: “I guess the reason why some young people may need to gain independence [is because of] family breakdown.”

“When young people need financial independence, its generally because they are unable to live in their family home for whatever reason. Also because of intergenerational poverty, so they’re in a family that is already struggling and that can be a contributor.”

The housing market is struggling to facilitate independence of young adults.

Hunt & Hunt’s Todd says rental unaffordability “has impacted her duties” as a property manager. The increase in rental prices has made her consider the repercussions for young people.

“Because the rental prices have increased so significantly, that is reflective of the interest rates that have increased. It’s a case of supply and demand — there’s much less supply and a lot more demand.”

Todd explains that high mortgage repayments due to increases in interest rates have forced some owners to sell their properties. This has a significant impact on the supply of rental properties in the market.

“Because interest rates are increasing, many landlords are then selling their properties which means there are not enough properties to be able to sustain the amount of people who need to rent,” Todd says.

“Since there are so many people who are trying to rent, renters are now offering higher amounts of money to try and secure a place.

“This is also pushing the rent prices up.”

Hunt & Hunt has units available at a lower price for around $370 per week. However, this only means more demand.

“The problem with our units is we are then getting three times the amount of people through inspections and only one person can be successful for the property,” Todd says.

“I’ve had families come up to me showing me photos of their children saying they’re going to be homeless.

“Hopefully prices settle down so that more investors are coming back into the market. That would mean that there would be more properties available for people to be able to apply for.”

Todd says the opportunities to secure a rental as a young person are low.

“Young people trying to rent won’t have the experience to get good rental references, and you’re also too young to be able to afford to buy a property because the property prices have increased so significantly.”

How is South Australia paying attention to young people during this crisis?

Uniting SA is a provider partner in the Adelaide North West Homelessness Alliance, which helps to reduce risk of homelessness through boarding houses, rental support and community housing. They run a specialised 24-hour residence available for young people.

Cox says: “It’s a way for young people who are stuck in the rental market themselves and trying to make it on their own.”

“Our houses have rules around them about how long they can be used. So, if they’re in transitional accommodation for example, then the rules are that you can’t be there for that long; it’s generally six months.”

According to Cox, more than half of young people who use Uniting SA’s accommodation services end up back in their family homes. The accommodation length for transitional housing needs to expand during this crisis. Otherwise, young people have little to no time to gain independence.

Centrelink is a significant issue for young renters, with no moves to increase Youth Allowance payments to keep up with increasing rental costs.

A proposed solution would be to lower the independent age threshold from 22 to 18 so that young adults who need to move out aren’t receiving money based on their parents’ income.

There are also calls for more public and social housing.

Data from Believe Housing Australia shows there has been a four per cent increase in the number of households on waiting lists for social housing across Australia, with approximately 224,000 households waiting.

Simms says: “We desperately need to invest in public housing and reign in soaring rent prices.”

On March 6, the Greens announced the party’s first Federal Election policy — a public property developer that would have the federal government build homes and sell and rent homes for below market prices.

“The Greens are campaigning to cap rents in line with inflation to stop prices skyrocketing out of control and provide renters with the same Cost of Living Concession as homeowners to help them through the cost-of-living crisis,” Simms says.

With many proposals and acknowledgements of awareness in comparison to few results and changes, actions need to be made immediately to alleviate this crisis — and Simms agrees.

“I want to see a rental market that sees housing treated as a fundamental human right, rather than a commodity. Every South Australian has a right to a roof over their head and a place to call home.”