What is life like for athletes after the final siren? Listen to the stories of post-professional players who learned to navigate their careers after the game. (Image: Jose David Cortes)

By Chelsea McLean | @chels.mclean

The whistle blows. The stadium drops silent with anticipation. You’re in the zone and you’re about to get the winning score for the team. This score is the only thing that matters; you’ve trained your entire life for this. And … you’ve got the goal! The crowd roars! The siren blows! The game is over — but what comes next? It’s time to hang up your guernsey and navigate life outside the game.

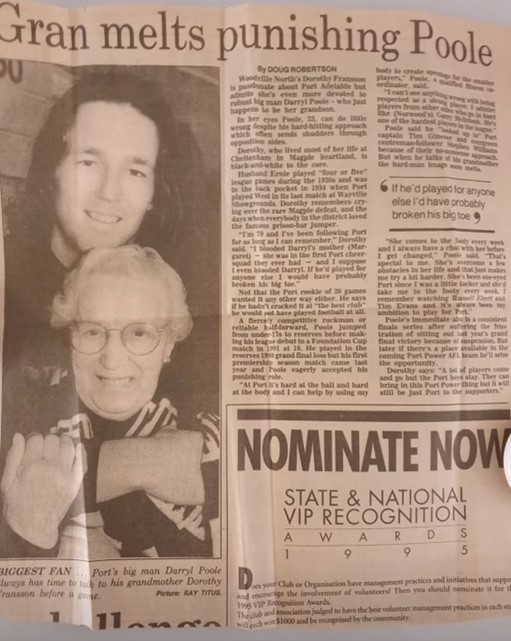

Elite sports careers generally last 10 years at best, with athletes departing from the game around the age of 34 according to Athlete365. With many working years left before they’ll reach Australia’s average retirement age of 67, how do athletes navigate life after the final siren? Curious about how post-professional athletes sustain their identity into adulthood, I had chats with two former players: one who detached himself from the game – former AFL player Darryl Poole – and another whose identity never left the field – former cricketer Mark Harrity.

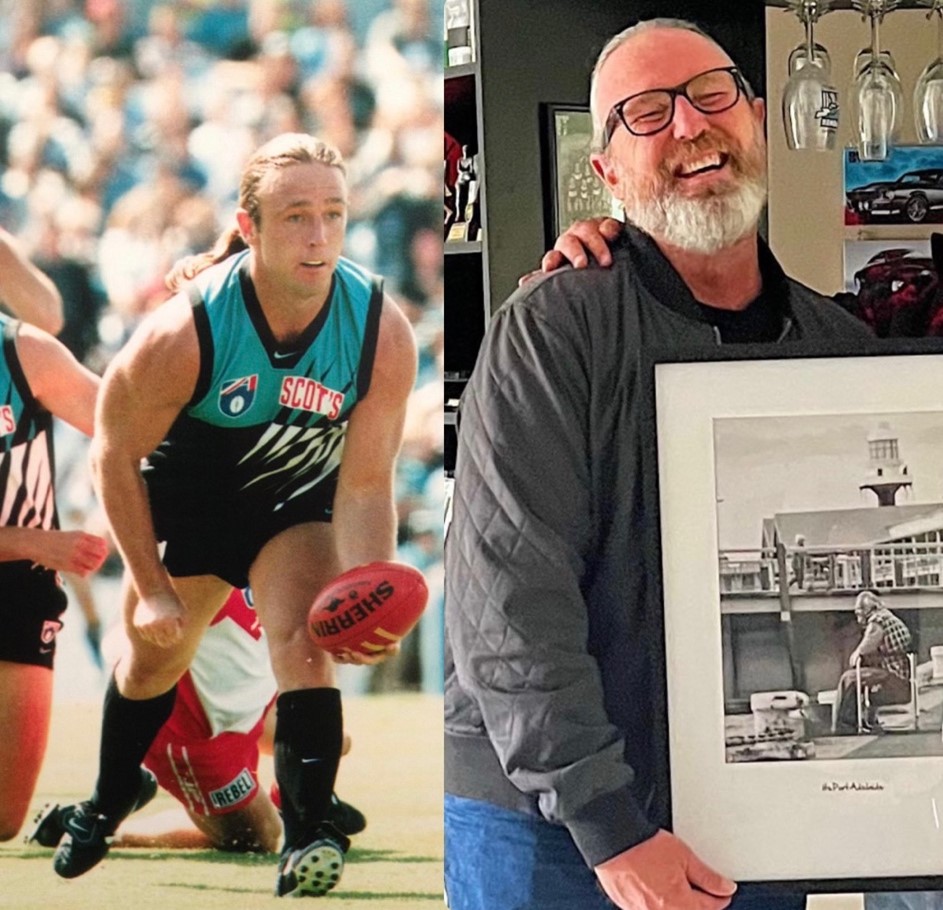

Still rocking his famous low ponytail from his Australian Football League (AFL) days, Darryl Poole, better known as “Pooley” to footy lovers, sits patiently on a wooden bench as I approach him.

“Pooley?” I ask just to make sure I am approaching the right guy (although I am almost certain from his iconic low ponytail). “Oh, hey!” Poole springs up with a bubbling mix of nerves and anticipation. “It’s nice to meet ya,” he says as he gives me a bear hug. His dry, grey beard and square glasses give him a wizardly look, contrasting his Aussie dad persona.

“So, how did you know footy was what you wanted to do?” I ask.

“I was born a local to the Port Adelaide area, so I’ve always loved Port, and I’ve always gone to the games with my grandparents,” Poole says with a big grin, accentuating his rosy cheeks. “Every Saturday we’d always pack lunch and then take our little deck chairs and go and watch the local Port Adelaide games. That inspired me to find my purpose and what I wanted to do. I just loved it.”

Poole joined the AFL when he was 24 and was delisted at the age of 28. “I was kind of getting towards the end of my career anyway,” he says. “And so really, I just feel fortunate that I’ve played in the AFL and got to represent the club.”

Towards Data Science notes that the lifecycle of an average AFL player is brief. Most AFL players are drafted at the age of 19 to 20 and tend to peak at the age of 22 to 24 years before being delisted.

A few days before chatting with Poole, I spoke with Joel Fowler, who teaches clinical exercise physiology at the University of South Australia. Fowler says: “If there is high athlete identity within an individual, then research shows us that’s fantastic performance-wise. However, post-retirement [this] creates a sense of loss within that individual, impacting their physical and psychological health.”

Poole says this “sense of loss” was exactly what he experienced after his time with the AFL: “Post-footy was a challenging time, because at 28, having [had footy as] my main focus in life, it was a tough period because I didn’t know what I wanted to do.” He fidgets with a dry, fallen leaf. “I knew I had some skills in the health and fitness industry, and I could work my way through that, but my body had given up. I was a little bit lost for a while, which is pretty common.”

Poole spent this time backpacking around the world for nearly a year. “I let my beard grow really long,” he says. “And my hair was crazy like some weird wild dude in the outback.” An image of Tom Hanks as Chuck Noland in Cast Away enters my mind.

“And, yeah, I just took a year off, just chillin’. I remember sitting in Malaysia under a palm tree on an island, and I was drawing. I thought I could travel for years and have cool experiences, but without purpose in life, there’s no guts. I knew I wanted to do something, so I came back to Adelaide and worked at some health and fitness centres.”

Poole’s transition to working in the health field wasn’t too difficult, as the AFL provided him some work experience on the side of his footy career. “I was lucky enough to work for a big health chain, which is Goodlife now,” he says.

Poole’s life took a turn when he picked up his camera and started taking photos. “This was a turning point in my life where I wanted to do something different,” he says. “My photography evolved into my freelance business, It’sPortAdelaide, which is about giving back to the community and giving voices to those who don’t have that platform. It took courage to create my business as this type of thing was out of my comfort zone. But I really enjoy it, and I feel a purpose in life with this.”

Fowler recognises the importance of finding other work avenues post-sport, just like Poole did. “Having other avenues or interests in life is useful because it helps post-players to not feel as lost,” he says. “Now, they’ve got the time and energy to direct towards all these other things and look at repurposing their identity and what fulfils them.”

Poole reflects on the challenges he’s endured through his full-cycle experience with athlete identity. “It’s just about fun — not just in sport, I think in anything,” he says. “It’s taken me 50 plus years to find out what I wanted to do. My passions when I was a 10-year-old are different than what they are now as a 52-year-old. I’m just having fun doing what I’m doing and hopefully trying to make a positive difference.”

Poole has pushed through many post-sport challenges, showing it’s truly possible for post-players to pursue anything. However, some people just never want to leave the field.

Can a former professional athlete thrive in the sporting field decades later? Curious, I reached out to Mark “Hags” Harrity, who played first-class cricket for South Australia and county cricket for Worcestershire before turning to coaching.

Harrity, now 50, looks like he is still immersed in the sport with his tall, muscular build. Everything he’s learned from cricket lingers; he smells like men’s Rexona — a scent familiar to those who’ve been in the men’s changerooms.

“To start us off, how did you get into cricket?” I ask.

“It was actually a decision between footy and cricket,” Harrity explains. “I played football at a very young age. Cricket was not so serious, as I played it more with friends in the street. I think it was more that my brothers played football and were really good at it, but I think I just wanted to do something different.”

Harrity experienced stress fractures during his time as a cricketer. “All I really wanted to do is play the game,” he says. “And then of course, you get injured and that’s not part of the deal — like, ‘hang on, where did that come from?’ And now, all of a sudden, you deal with all those sorts of things. Unfortunately, it’s a common thing.”

Harrity’s injuries set him back, but did not lead to his retirement. He was 30 when he was taken off the England and Wales Cricket Board after a personal incident. Harrity then pursued his dream from his school days and got a job at a graphic arts company. However, this only lasted five years as he realised he wanted to get back into cricket. Harrity drew back to the sport like a magnet — not as a player, but as a coach. His athlete identity is unbreakable.

“By the time I retired [from] cricket, I did everything from being the bowling coach to the strength conditioning coach, which I actually studied strength and conditioning separate from the club,” he says. Harrity is now the head coach at the Darren Lehmann Cricket Academy and the West Torrens District Cricket Club. He is also a bowling coach at the South Australian Cricket Association.

Although Harrity has sustained a living from sport, he still recommends taking up a plan B. “You’ve got to have other avenues,” he says. “I’ve got other hobbies and interests. I like art and I’ve always loved drawing. I think that these days, sport clubs are much better in facilitating players for life.”

This is true; the Australian Cricketers’ Association offers education grants, workshops and courses to help prepare players for life after cricket. The AFL Players’ Association also offers education support services for players who want to study. And research with the Australian National Rugby League found players with higher levels of engagement in pre-retirement programs are more likely to enjoy success in their sporting careers. This is because the pressure to base their identities exclusively on sports are reduced.

Australian sports organisations are now much better at preparing players for retirement, showing that life after the final siren doesn’t have to be complex after all. Taking up a side goal can save you for life after you pack away your guernsey.

However, if you do get stuck in the void of uncertainty, it’s post-players like Poole and Harrity that show you don’t need to have everything sorted to be successful after sports. Poole decided to take up photography after contemplating his purpose in life, whereas Harrity found ways to translate his athlete identity into his older age. Your legacy doesn’t end with the game; it ends when you want it to end.