With claims that youth crime rates are rising across metropolitan areas, Australian politicians are proposing harsher punishments for children as an answer to the ‘crisis’. But is this the only option we have? And is there a crisis at all? (Image: Emiliano Bar)

By Shannon Blyth | @ShannonBlyth

In scenes not dissimilar to the critically-acclaimed series Adolescence, Adelaide Youth Court duty solicitor Rochelle Weston sees children who have been arrested every day.

Weston spends these days speaking to children, some as young as 10, who have been charged with offences including assault, robbery, arson and criminal trespass.

She is the children’s voice to the court, listens to their experiences, assists them in applying for bail and explains the punishment they could face for the crime they are accused of.

Weston works with the children and other stakeholders in their lives, such as social workers or child protection, to see if there is a suitable address for bail or if a child must remain in custody for a longer period.

Detaining isn’t the answer for young offenders, according to Weston.

The intention of the youth court is to divert people from the system and, when the court process is used effectively, “this can be done”.

“If you think that treating youths like adults is effective then I’d invite you to come and spend the day at the youth courts and see what we’re actually dealing with.”

Weston believes if people better understood the system, they would also better understand its goals for correctional guidance.

The objective of the Young Offenders Act 1993 (SA) is to ensure support for young offenders to develop into responsible members of society. The legislation ensures that magistrates do not unnecessarily remove children from their family or schooling when deciding on their penalty.

The legislation guiding decisions in the youth court is also influenced by the common law principle of doli incapax, where a child between 10 and 13 is presumed incapable of committing a crime due to their inability to understand wrongness. The prosecution must prove the child knew they were doing something wrong.

Is there really a youth crime crisis?

In 2024, the Queensland Liberal National party gained nation-wide attention by popularising the term ‘adult crime, adult time’ during an alleged youth crime crisis. Policy proposals by the party intend to give children who commit crime the same prison sentence as an adult for over 20 offences, including murder, serious harm and stealing vehicles. This would mean that a child aged 10 charged of murder could face a sentence of life imprisonment.

The snappy slogan has been criticised for disregarding factors that cause youth crime, says the communications officer of the Youth Advocacy Centre in Queensland Shannon Cant. The centre provides young people with legal support, family assistance, bail programs, and help in finding stable housing for those who have just left detention centres.

Cant challenges the idea that detention is the solution.

“This whole ‘adult crime adult time’ saying disregards that a lot of these youths come from potentially broken families or government care,” she says.

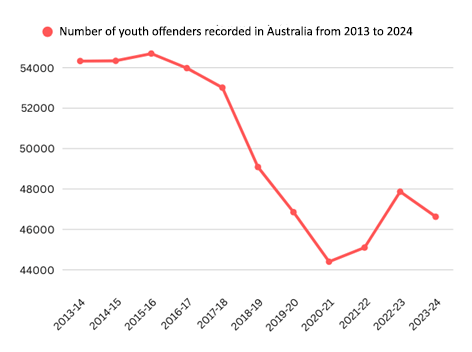

“When [the media] say that youth crime is out of control, we actually can see that, with a few ups and downs over the last decade, it’s going down.

“It’s just that the hotspots create a lot of concern.”

In the latest recorded crime release by the Australian Bureau of Statistics from the 2023–24 financial year, there were over 46,000 youth offenders recorded in Australia — a total of 13.71 per cent of total offenders across the country.

However, when looking at past statistics, the trend demonstrates a steady decrease in recorded youth offenders over the past 10 years.

Number of youth offenders recorded in Australia from 2013–2024 (source: ABS data)

Cant says these rates cannot be discussed without considering factors that lead to criminal behaviour.

“A misconception is the idea that they wake up one day and this well-adjusted young person picks up a machete and does something heinous,” she says.

“It’s discounting all the things we know impact the outcomes for young people like home life or their school life.”

Why do young people offend?

There are a myriad of reasons why young people offend, Louisa Hackett says.

Hackett, who now works in private forensic psychology, was previously the principal psychologist for Youth Justice within the Department for Human Services in South Australia. She cites the importance of using different approaches in working with young people.

“It is really important that when you are working with children and young people that you adapt your approach because their neurodevelopmental stage is obviously very different to that of an adult,” Hackett says.

“They are still learning, still developing and still growing and many young people who become involved in the system actually have what’s called developmental delays for a range of reasons, including neurological conditions, as well as a lot of experiences of child abuse and neglect.

“All of those things affect a developing brain.”

Hackett says other factors can include difficulty with emotional regulation and a lack of solid attachment from supportive adults around them.

Another prominent factor in youths offending is the accessibility of education, and, when enrolled, engagement with school activities.

Managing children’s engagement with school is an everyday struggle for secondary teacher Renee Nikoloudi, who works with vulnerable students in Port Pirie. Her focus, unfortunately, can often be disciplining rather than teaching.

“I believe schools do have a behavioural crisis,”

“Ten to 15 years ago classrooms would only have one to two kids misbehaving, whereas today classrooms have one to two kids doing the right thing,” she says.

While educators work to engage and manage children’s behaviour in schools, Nikoloudi says the parenting and lack of stability in a house for a child can be a strong factor in acting out at school.

“I strongly believe bad parenting, abuse or neglect, [and] kids in care systems, are huge contributors to children misbehaving,” she says.

“Most of the students I deal with display behaviours that make more sense to me after I have contacted home or am aware of their family situation.”

Children left without a stable home

Exposure to and experiences of trauma and abuse have a substantial impact on a child’s development.

Hackett has seen children who have experienced severe neglect and chronic emotional, physical and sexual abuse throughout their lives.

“They’ve not had a stable and supportive adult around them,” she says.

“Many young people have been removed from their families by the Department of Child Protection (DCP) because of the level of abuse and neglect that they’ve been exposed to.”

In March 2025, 4,878 children lived in government care in South Australia and 14 per cent of them were in residential care. Children in residential care homes are placed with other children who have been removed from their families and supported by rostered workers with a combination of day and overnight shifts.

Many of Weston’s clients have lived in residential care homes since a young age and are traumatised youths.

“Imagine when you were young, and you had a fight in your house and maybe you threw a plate, and it smashed a window,” she says.

“You got disciplined in your house and maybe you got grounded where you had something taken away from you.

“It is unlikely that your parents called the police and reported property damage and you were charged.

“In DCP care homes, that is what will happen.”

The emotional harm children experience in these homes can pose a challenge in providing them with support.

“I have a lot of kids emotionally switched off because of the trauma they have experienced, that’s really devastating, and they aren’t receptive to support,” she says.

“Those things could be anchored in their life and to turn them around from offending behaviour can be almost too hard to reach.

“They aren’t experiencing a normal childhood experience like you or I had.”

Combatting youth crime

South Australia offers services that provide legal information and encourage young people to turn their life around. These include travelling education officers Jana Gomes and Paul O’Connor from the Legal Services Commission of South Australia.

Gomes and O’Connor visit schools, DCP homes and the Kurlana Tapa Youth Justice Centre to teach children about consent and healthy relationships, drugs and alcohol, traffic offences, police interaction, their rights and responsibilities online, and justice and change.

“The purpose of them is to empower young people with knowledge to keep them safe and make better choices and hopefully they don’t end up in the court system,” Gomes says.

She and O’Connor understand that one session may not resolve the issue.

“I suppose one thing we consider is that us coming in for a one-hour session may not in itself result in wholesale change. But the more that these messages are out there and being repeated then the more [young people] are thinking,” O’Connor says.

Youth advocate Daniel Principe says providing role models to young people can help to give them a chance to change their life.

Principe helps young men reflect on who they are becoming and visits high schools to ask them to consider “if the ideas they have adopted about men, women, relationships and sexuality are healthy and helpful or harmful to others”.

Encouraging safe, social physical activity has also had positive effects for young people.

Lighthouse Youth Projects senior mentor Joey Brooks aims to give young people a more positive outlook on life and have them source the adrenaline criminal activity gives through less anti-social and illegal behaviour.

“Young people need to thrill seek and some choose to do that in a criminal way,” he says.

“But if you can teach them somehow to get that same thrill by using a bike, it can be a good thing.”

Having social activities can change the path of a young person’s life, she says.

Do youth offenders deserve a chance to change?

The issue of youth crime is complex and a place where people may believe the system is too lenient.

Weston says repeat offenders have clear issues in their behaviour, and she hopes their matters can be dealt with in the youth court to prevent them being adult offenders.

“You would like to think that the work has been done for young people as they have entered into the system but it’s hard to determine if this will work for everyone,” she says.

“I hope that the system can help them understand the severity of their actions, give an appropriate penalty and they are not seen in the system again.”

Family conferences, involving the young offender, their family and a magistrate, within the youth court go some way in promoting rehabilitation. The purpose of this meeting is to discuss possible consequences which may include an apology to the victim, payment of compensation or undertaking community service.

The intention of this program and other diversion programs in the youth court is for young people to take accountability for their behaviour.

Family conferences can help mend a family relationship and give a young person the chance to make better choices.

“The victim has the right to attend, and my 14-year-old client may have to sit across from the person they’ve assaulted and apologise to their face,” she says.

“That’s pretty significant and quite intimidating.”

Weston has seen success in youth clients that have completed the family conference.

“Success for me is I resolve your matter and I never see you again,” she says.

“If you make a one-off mistake and learn from it then you should have the right to be diverted out of courts to a family conference and have your penalty dealt with without impacting your criminal record for the rest of your life.”