Amid accusations of opaque ownership and unfair contracts, an independent governing body has been proposed to overhaul South Australia’s nearly 50-year-old container deposit scheme and wrest control from the profit-driven beverage industry and their subsidiaries. (Image: Jacinta Round)

By Jacinta Round | @calamityjacinta

Although recycling depots are the public face of South Australia’s container deposit scheme (CDS), some recycling operators say current legislation does not guarantee they are adequately paid for their services by the companies controlling the scheme.

McLaren Vale Recycling Centre owner* William Billing says the handling fee paid to his depot has not risen to accommodate growing operation costs such as wage increases.

“We have to pay our employees more, but we still have to give that 10 cents out,” he says.

Depots like Billing’s rely on the handling fee paid to them for collecting and sorting 10-cent containers.

The McLaren Vale Recycling Centre is one of around 132 depots where South Australians can collect a 10-cent refund by returning beverage containers eligible under the CDS.

In South Australia, current legislation requires beverage manufactures to fund businesses known as “super collectors” to operate the CDS. As the mediators between beverage manufactures and recycling depots, super collectors are responsible for paying handling fees to depots.

Under the Environment Protection Act 1993, the CDS is self-governed, meaning there is no mechanism to regulate fair negotiation and transparency of handling fees paid to depots.

Beverage containers are manually processed by recycling depots like the McLaren Vale Recycling Centre (Image: Jacinta Round).

Alongside his wife and two sons, Billing has made a living from his family-owned depot for nearly 12 years. Now, due to insufficient handling fees paid to him by the super collectors, Billing says his business is “starting to feel the pinch”.

“We get the same handling fee we got three or four years ago. It goes up a smidgen, but it doesn’t go up enough,” Billing says.

Since it began in the 1970s, South Australia’s CDS has become a matter of state pride as the nation’s first beverage container refund system.

By incentivising recycling of beverage containers, the CDS has helped keep bottles and cans out of landfill and the litter stream for almost 50 years. Data published by the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) shows that over 74 per cent of beverage containers sold in South Australia in 2023–2024 were recovered through the CDS.

Head of operations at Scout Recycling Centres Steve Hastwell says Scouts SA “went out on a limb” and bought a scrapyard for use as a beverage container collection point in 1977.

“In the first year it didn’t make any money, and everyone was concerned but now it’s grown to over 11 depots and a [collective] turnover of some $26 million in recycling,” Hastwell says.

Scout Recycling Centres are not-for-profit businesses that help fund Scouts SA initiatives. Hastwell says they are currently collaborating with the Hutt St Centre to provide employment opportunities at their depots for disadvantaged South Australians.

“Unfortunately, our handling fees haven’t increased as much as costs over some 40 years of business,” he says.

While Hastwell welcomes wage increases, he says it’s harder for Scouts to make money from their recycling centres.

Neville Rawlings is the president of Recyclers of South Australia Incorporated, also known as Recyclers SA, an association representing over 90 recycling depots in the state — including Billing’s.

“When depots thrive, the CDS benefits through higher material recovery rates, better recycling outcomes, and stronger economic returns for the state,” Rawlings says.

According to an explanatory guide published by the EPA, despite their role as the government-based regulators of the CDS, the EPA’s oversight is limited under current legislation. This means the EPA is unable to intervene in contract negotiations between super collectors and the depot network.

In 2019, the EPA began a review to address “embedded governance challenges” arising from the scheme’s self-governed nature.

In September 2024, draft legislation was proposed by the EPA to replace the super collector system with a not-for-profit, independent scheme coordinator to govern the CDS and negotiate contracts between beverage manufacturers and recycling depots.

How does the CDS work in South Australia?

With Tasmania’s Recycle Rewards scheme starting on May 1, 2025, each Australian state and territory now has its own individual beverage recycling legislation.

South Australia’s CDS is an industry-led product stewardship scheme, where both manufacturers and consumers pay for the recycling of products.

The EPA refer to the CDS as a “funded collection system” where “beverage suppliers establish an individual contract with a super collector and pay a fee to cover the 10-cent refund and ‘handling’ of containers,” which is passed onto depots by super collectors.

Three super collectors currently coordinate the scheme: Statewide Recycling, Marine Stores and Flagcan Distributors.

General manager of Marine Stores Craig Marshall says the super collector has acted as the middle party of the 10-cent deposit scheme for close on five decades.

“If you’re a beverage manufacturer … to register your container you have to have an agreement with one of the super collectors,” Marshall says.

Craig Marshall at the Marine Stores warehouse with CDS aluminium cans ready to be sent offshore for recycling. (Image: Jacinta Round).

“If company X has an agreement with us, when we then go to the depot side, the containers that company X produces then have to come to us and we’re responsible for recycling those containers,” he says.

The 10-cent refund is passed on to the consumer in the beverage purchase price.

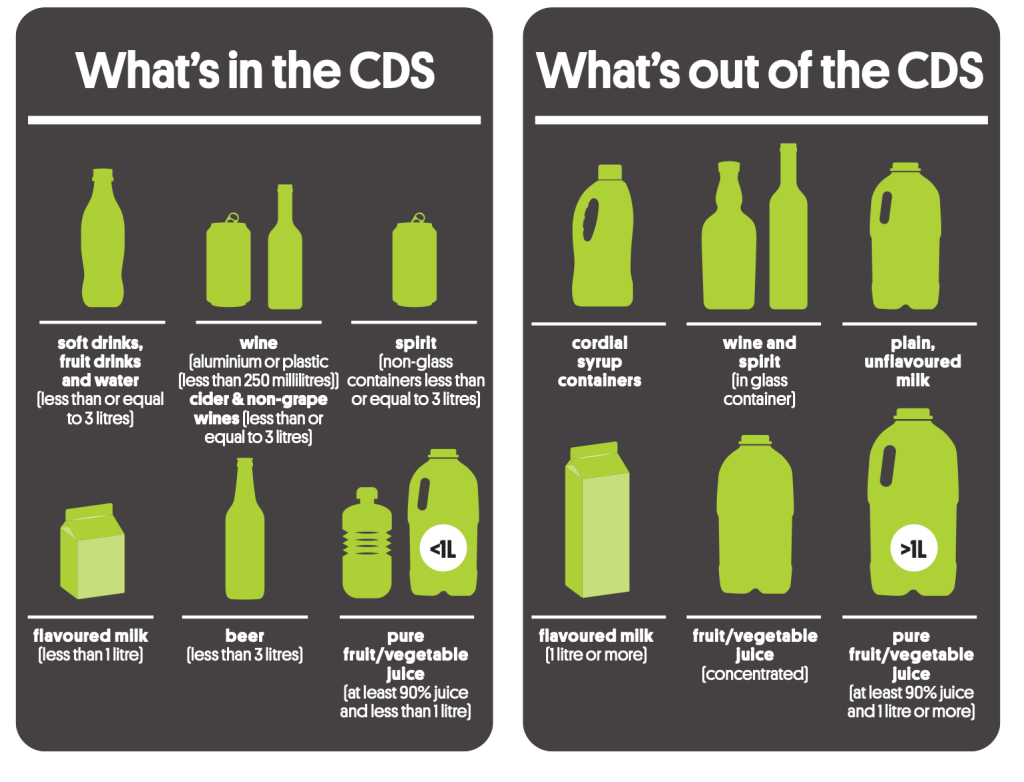

The South Australian government has indicated they will expand the existing scheme to include all beverage containers under 3 litres (excluding plain milk packaging) by 2027.

Beverage container types eligible under SA’s current container deposit legislation. (Image: Environment Protection Authority South Australia).

When eligible containers are returned by consumers to a recycling depot, they are manually counted, sorted, and bundled up, ready to be picked up by super collectors.

A discussion paper by the EPA states that contracts require super collectors to reimburse depots for the 10-cents they have refunded to community members and pay a handling fee “to fund container collection, sorting activities and transport costs incurred by the collection depot”.

If CDS products are placed in kerbside recycling bins, containers are separated from other household recycling at material recovery facilities (MRFs) and returned to depots.

The refund is paid to the consumer or MRF by the depot who are then reimbursed by the super collectors.

The CDS’s transparency problem

Billing says there is a noticeable difference in the handling fee paid to his depot by the two major super collectors, Statewide Recycling and Marine Stores.

“One super collector is better than the other. Why they’re not the same is beyond me because the cans are the same, the bottles are the same,” he says.

Marshall says this can be explained by confidentiality and competitive pricing between super collectors.

“We’re technically competitors,” he says.

“We all have different pricing based on our operation, I would imagine they’re fairly similar, but I don’t know because it’s all commercially sensitive.”

Shannon Doherty-Andall is the sustainability manager at the Australian Beverages Council Ltd (ABCL), the sole peak body representing non-alcoholic beverage manufacturers in Australia.

When asked about handling fees, she says it makes sense that depots are feeling disadvantaged due to South Australia’s CDS having “zero visibility”.

“South Australia is a bit of a black hole for us with the three super collectors that have their own commercial and confidence needs,” she says.

Unlike container deposit legislation in other jurisdictions, Doherty-Andall says South Australia having multiple super collectors makes the CDS complicated for beverage suppliers.

“With the super collector model, there are these three private companies making contracts how they like,” she says.

She says the ABCL is unable to determine whether the beverage manufactures they represent are “getting the same rates or how … they are being treated”.

In 2018, Recyclers SA were granted collective bargaining authorisation on behalf of the depots they represent by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

This allows them to officially assist their members in negotiating contracts, including those that determine handling fees, with super collectors for 10 years.

The ACCC’s final determination, in relation to the Recyclers SA’s application, says depots raised concerns that their contracts with super collectors had “expired or not been recently renegotiated” and “as small businesses negotiating with a larger counterparty, they face difficulties in individually negotiating changes to contracts”.

Marine Stores formally objected to Recyclers SA’s application to the ACCC.

Rawlings says that the super collector model means the CDS is governed by opaque companies “established by beverage industry subsidiaries”.

“Allowing the beverage industry to influence the CDS introduces conflicts of interest that would prioritise beverage industry profits over environmental outcomes,” he says.

Marshall says beverage companies Lion and Coopers are both “directly involved in Marine Stores” as shareholders and have been “since its inception”.

According to the Department of Primary Industries and Regions, Coopers is the largest Australian-owned brewery.

Rawlings says “the CDS needs to reflect the aspirations of the community, and not those of the beverage industry”.

CDS review

The EPA’s review into the CDS began six years ago; stakeholders are still waiting for any sort of legislative change to be enacted.

The initial scoping paper of the reviewinvolved over 1,000 respondents including CDS stakeholders and members of the public. All interviewees in this article say they had some level of engagement with the review.

According to the summary report in response to the scoping paper, governance was a key issue raised by stakeholders.

The outcome of the review was the Draft Environment Protection (Beverage Container Deposit Scheme) Amendment Bill 2024, released by the EPA for feedback in September last year.

A spokesperson from the EPA says “proposed changes to scheme governance, including the appointment of a not-for-profit scheme coordinator and therefore the removal of super collectors from the SA scheme, seek to improve transparency around container flows, financial flows, and scheme fees”.

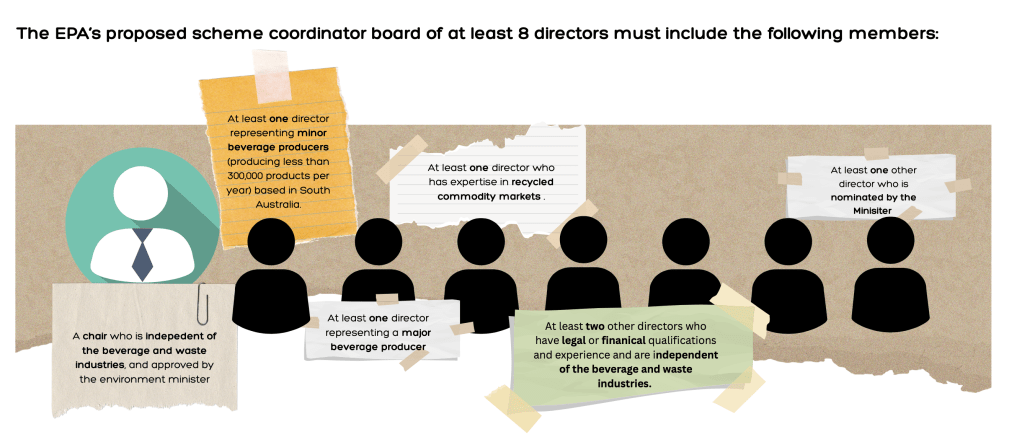

According to the EPA’s Explanatory Guide to the Draft Amendment Bill, legislation changes would require South Australia’s environment minister to appoint a non-for-profit board to govern the scheme.

The board would comprise of at least eight members with specific backgrounds including representatives from the beverage industry and the depot network.

The prescribed functions of the scheme coordinator would involve managing agreements with beverage suppliers and recycling depots and setting the scheme price.

The Explanatory Guide to the Draft Amendment Bill states: “in response to a long history of pricing disputes between participants in the current scheme, the draft Amendment Bill proposes a scheme price review mechanism for the Essential Services Commission of South Australia (ESCOSA)”.

Handling fees paid to recycling depots are included in the EPA’s definition of “scheme price”.

Response to the draft bill

The EPA’s draft bill has received a mixed response from stakeholders.

Since there is no single association representing recycling depots, Billing is concerned that depots like his will not have enough of a voice if the scheme moves to a not-for-profit coordinator.

“We aren’t a collective,” he says of the depot network.

The proposed composition of the board designates a position for “at least one director representing a container refund point operator association in South Australia”.

Depot associations like Recyclers SA only represent a portion of the diverse network of recycling depots.

“We’re not getting much of a say now, so we don’t know what we’re going to get if we go to a single [coordinator] and that’s the problem,” Billing says.

Recyclers SA are not in favour of the draft bill. Rawlings says it does not provide “adequate protections” for Recyclers SA’s members.

“If anything, the new draft bill could make the situation worse … by failing to provide a guarantee to depots that the current handling fees will not reduce,” he says.

Rawlings proposes the appointment of a South Australian agency, such as Green Industries SA, who already have the capability to provide “independent oversight, with an established skills-based board” to oversee the CDS.

Hastwell says Scouts SA support a not-for-profit scheme coordinator but would like to see “strong governance” from the EPA.

“We’d like more frequent reviews of handling fees,” he says, referring to the proposed ESCOSA price review.

“As long as there is equal representation from industry associations like Recyclers SA, from beverage manufacturers and from the not-for-profit sector where you’ve got people like us running recycling … we’ll be fine,” he says.

Marshall says Marine Stores support the scheme objectives proposed by the draft bill.

“They’re good for the scheme, they’re good for South Australia. They can’t be achieved with what we’ve got but they can be achieved with a singular coordinator,” he says.

Doherty-Andall says the ABCL endorse the not-for-profit coordinator model used by the container deposit legislation of other states including Queensland and Western Australia.

“When you have a single scheme coordinator it’s almost like a quasi-regulatory body and you can see … how the money is used,” she says.

When asked, the EPA was unable to provide a timeframe for the draft bill’s introduction to parliament.

Billing’s hope is that the future of the CDS is more transparent, not only for the sake of his family business but for the sake of Australia’s inaugural beverage container refund system.

“What we do in South Australia, is we do a lot of recycling. We feel good about it,” he says.

*Since the publication of this article, Billing no longer owns McLaren Vale Recycling Centre.